Richard Allen Founder of the African Methodist Church in Philadelphia

Richard Allen:

One of America’s Black Founding Fathers

“I hope the name of Dr. Benjamin Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston will never be forgotten among us. They were the two first gentlemen who espoused the cause of the oppressed, and aided us in building the house of the Lord for the poor Africans to worship in. Here was the beginning and rise of the first African church in America.”

Richard Allen and Dr. Benjamin Rush

The above words were written by the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, Reverend Richard Allen himself- penned in his autobiography which was published in 1833, two years after his death. As many know, Dr. Benjamin Rush was one of America’s founding fathers. Considered the founder of American medicine, Dr. Rush was also founder of the Philadelphia Bible Society, and founder of an anti-slavery movement that started nearly 90 years before President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation which ended slavery in America.

Dr. Rush was an associate of Francis Asbury. And so was Richard Allen.

Richard Allen Early Years and Francis Asbury

Allen more than likely first met the young British preacher, Francis Asbury, at the age of 12 when Asbury first visited the home of Jesse Chew, brother of Allen’s owner, Benjamin Chew. Benjamin Chew was the personal lawyer to the family descendants of William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania. He was a Quaker and Chief Justice of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The Chew home which Allen grew up in at an early age was frequented by many of America’s founding fathers. Men like John Adams, Dr. Benjamin Rush, and Benjamin Franklin were close friends with the Chew brothers.

At some point, more than likely around 1768 or slightly later, eight-year-old Richard Allen, along with two of his siblings and his parents, were sold to Stokeley Sturgis, a man who Allen describes in his autobiography as: “an unconverted man … but he was what the world called a good master. He was more like a father to his slaves than anything else. He was a very tender, humane man. My mother and father lived with him for many years.” Uniquely, with Allen’s new residence within walking distance of the one-thousand-acre Chew farm, this sale of Allen to Sturgis did not keep Allen from interacting with the Chew family, especially his former owner, the wealthy lawyer, Benjamin Chew.

Stokeley Sturgis was a struggling planter. His farm consisted of roughly two hundred acres situated a few miles west of Delaware Bay in Kent County, Delaware, at the junction of Muddy Branch and Little Duck Creek. The Sturgis farm, which lay about six miles northeast of Dover, Delaware, was only one mile from Benjamin Chew’s farm, Whitehall. As odd as it may sound to those of us who live in the 21st-century and realize the depravity of human slavery- this sale of Richard and part of his family by friend of the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Chew, to Sturgis- must have made sense to Chew and Sturgis when you consider that not only would the separated family members be within walking distance of each other, but also that Chew, on a regular basis loaned money and help to the lesser farmer, Sturgis.

Richard Allen Christian Conversion and Early Preaching and Evangelizing

Sometime before the age of twenty, more than likely the age of seventeen, around 1777, Richard had a strong feeling that his life did not square with God. According to Gary B. Nash, in his April 1989 article in the William and Mary Quarterly, New Light on Richard Allen: The Early Years of Freedom, Allen’s spiritual awakening may have been prompted by Sturgis’ financial difficulties. Allen, in his retelling of the events to his son, “recalled that Sturgis was ‘much in debt’ in 1780; some evidence of this can be found in the 300 pound loan Sturgis negotiated from Benjamin Chew in 1777 and also in documents, drawn up at the time of Sturgis’s death many years later. These documents described the marginal condition of Sturgis’ farm.

‘Brought into difficulty,’ Allen told his son that Sturgis had sold Allen’s mother with three of her children before 1780, probably about 1776. Again, according to Nash, in 1777 Allen experienced a religious conversion, in part inspired, it appears, by the desolation he felt at the loss of his mother and siblings. Allen related that he joined ‘The Methodist Society’ and attended class meetings under John Gray for several years ‘in the forest’ at the farm of Benjamin Wells. Gray was Well’s son-in-law, and from early deeds it is possible to locate Wells’ property less than a mile northwest of the Sturgis farm on the south side of Little Duck Creek.”

This awareness was also brought about by several conversations and questions posed by and to Christians whom Allen was exposed to. For a time, he struggled with this. In his autobiography, he describes his conversion: “I went with my head bowed down for many days. My sins were a heavy burden. I was tempted to believe there was no mercy for me. I cried to the Lord both night and day. One night I thought hell would be my portion. I cried unto Him who delighted to hear the prayers of a poor sinner; and all of a sudden my dungeon shook, my chains flew off, and glory to God, I cried. My soul was filled. I cried, enough for me–the Saviour died. Now my confidence was strengthened that the Lord, for Christ’s sake, had heard my prayers, and pardoned all my sins. I was constrained to go from house to house, exhorting my old companions, and telling to all around what a dear Saviour I had found.”

Allen continues: “Our neighbours, seeing that our master indulged us with the privilege of attending meeting once in two weeks, said that ‘Stokeley’s negroes would soon ruin him’; and so my brother and myself held a council together that we would attend more faithfully to our master’s business, so that it should not be said that religion made us worse servants, we would work night and day to get our crops forward, so that they should not be disappointed. We frequently went to meeting on every other Thursday; but if we were likely to be backward with our crops we would refrain from going to meeting. When our master found we were making no provision to go to meeting, he would frequently ask us if it was not our meeting day, and if we were not going. We would frequently tell him, ‘No, sir, we would rather stay at home and get our work done.’ He would tell us, ‘Boys, I would rather you would go to your meeting: if I am not good myself, I like to see you striving yourselves to be good.’ Our reply would be, ‘Thank you, sir; but we would rather stay and get our crops forward.’ So we always continued to keep our crops more forward than our neighbours; and we would attend public preaching once in two weeks, and class meeting once a week. At length our master said he was convinced that religion made slaves better and not worse, and often boasted of his slaves for their honesty and industry.”

In time, Allen began to attend Methodist church services in the famed Delaware Methodist church, The Forest. The Forest was the first Methodist church in Delaware. It was located at the home of Benjamin Wells. Allen attended meetings held by class leader, John Gray.

Worried for the salvation of his aging owners, Allen asked permission for the Methodist preachers to visit the Sturgis home. Stokely Sturgis agreed and Allen summoned Methodist preacher, John Gray, to preach to the Sturgis family along with their slaves. A regular Wednesday evening preaching stop was quickly organized.

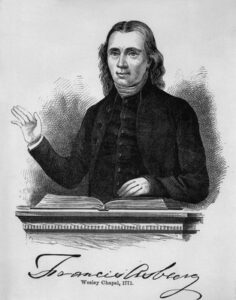

Richard Allen, Francis Asbury, and Freeborn Garrettson

Francis Asbury 1771

In August of 1779, the American leader of the Methodist movement, Francis Asbury, visited the Wells’ Farm. After preaching to the Wells family, Asbury traveled the short distance to the Sturgis farm. There, according to Nash’s article mentioned above, “Allen and his brother and sister were no doubt in attendance, and it may have been at this first encounter with the nineteen-year-old slave that Asbury saw the spark of genius that six years after would impel him to invite Allen to travel with him on his ceaseless journeys through the South and the mid-Atlantic region.”

Several months after Asbury’s visit to the Sturgis Farm, the young Methodist circuit-riding preacher from Maryland, Freeborn Garrettson, arrived to give the Wednesday evening message. The message was spot on. Allen’s account is below:

Freeborn Garrettson

“… At length Freeborn Garrettson preached from these words, ‘Thou art weighed in the balance, and art found wanting.’ In pointing out and weighing the different characters, and among the rest weighed the slave-holders, my master believed himself to be one of that number, and after that he could not be satisfied to hold slaves, believing it to be wrong. And after that he proposed to me and my brother buying our times…”

Freeborn Garrettson’s sermon was not only spot on for Sturgis, but Freeborn himself, a once wealthy Maryland slave owner, he experienced those very same words in a dream. The dream not only brought self-condemnation to Freeborn for owning slaves, but it was also the inspiring incident to move Freeborn to free his family’s slaves. This move of freedom fell upon much disagreement with his family and neighbors. Shortly after this freeing act, Freeborn himself would join Francis Asbury and the Methodist preachers on horseback.

The following three paragraphs are directly from Richard Allen’s autobiography in regard to Sturgis’ being inspired to free his slaves:

“And after that he proposed to me and my brother buying our times, to pay him sixty pounds gold and silver, or two thousand dollars continental money, which we complied with…”

“We left our master’s house, and I may truly say it was like leaving our father’s house; for he was a kind, affectionate, and tender-hearted master, and told us to make his house our home when we were out of a place or sick. While living with him we had family prayer in the kitchen, to which he frequently would come out himself at time of prayer, and my mistress with him. At length he invited us from the kitchen to the parlour to hold family prayer, which we attended to. We had our stated times to hold our prayer meetings and give exhortations at in the neighbourhood.“

“I had it often impressed upon my mind that I should one day enjoy my freedom; for slavery is a bitter pill, notwithstanding we had a good master. But when we would think that our day’s work was never done, we often thought that after our master’s death we were liable to be sold to the highest bidder, as he was much in debt; and thus my troubles were increased, and I was often brought to weep between the porch and the altar. But I have had reason to bless my dear Lord that a door was opened unexpectedly for me to buy my time, and enjoy my liberty. When I left my master’s house I knew not what to do, not being used to hard work, what business I should follow to pay my master and get my living. I went to cutting of cord wood. The first day my hands were so blistered and sore, that it was with difficulty I could open or shut them. I kneeled down upon my knees and prayed that the Lord would open some way for me to get my living. In a few days my hands recovered, and became accustomed to cutting of wood and other hardships; so I soon became able to cut my cord and a half and two cords a day. After I was done cutting, I was employed in a brick-yard by one Robert Register, at fifty dollars a month, continental money. After I was done with the brick-yard I went to days’ work, but did not forget to serve my dear Lord. I used oftimes to pray sitting, standing, or lying; and while my hands were employed to earn my bread, my heart was devoted to my dear Redeemer. Sometimes I would awake from my sleep preaching and praying. I was after this employed in driving of wagon in time of the continental war, in drawing salt from Rehobar, Sussex County, in Delaware. I had my regular stops and preaching places on the road. I enjoyed many happy seasons in meditation and prayer while in this employment.“

Richard Allen Purchases his Freedom

Richard and his brothers knew they had to pay off their freedom sooner than the planned five year period, mostly in fear that the elderly Sturgis would die before they paid for their freedom. With Sturgis’ financial struggles with debt, in the event of his death, Allen and his brothers would be sold again to pay off the debt. They acted quickly.

With the first payment due in February of 1781 and with the American Revolutionary War not over, Allen took work in a brickyard. In addition, he began chopping wood. In time, he was able to gain more income delivering salt from Rehoboth, in Sussex County, delivering the needed substance to Dover. What blossomed was his business acumen and financial stewardship. By August of 1783, just over three years into the five-year program, Richard Allen was able to pay for his freedom. According to Nash, “… he also presented the struggling Sturgis with a gift of eighteen bushels of salt, worth a guinea per bushel at the time, in consideration ‘of the uncommon kind Treatment of his Master during his Servitude.’ Such a gift, representing at least half a year’s wages for a common laborer…”

Richard Allen Itinerant Preacher

With the end of the conflict with England and his hard-earned freedom from slavery, Richard Allen began his itinerant career. As a traveling preacher on foot, Allen began in the Wilmington, Delaware area. Shortly after beginning to itinerate, like Francis Asbury, Richard Allen became sick. Very sick was Allen. From his autobiography: “Shortly after I was taken sick with the fall fever and then the pleurisy.” He struggled with these illnesses for several months until the fall of 1783.

On September 3rd, 1783, Richard Allen left Wilmington, Delaware and headed for West Jersey. He would remain there, preaching the Gospel on foot until the spring of 1784. About this time, Allen meets and begins to travel with Methodist itinerant, Benjamin Abbott.

According to Allen, Benjamin Abbott was a kind man. From Allen’s autobiography: “I then became acquainted with Benjamin Abbot, that great and good apostle. He was one of the greatest men that ever I was acquainted with. He seldom preached but what there were souls added to his labour. He was a man of as great faith as any that ever I saw. The Lord was with him, and blessed his labours abundantly. He was as a friend and father to me. I was sorry when I had to leave West Jersey, knowing I had to leave a father.”

Abbott’s amazing testimony was mostly what was used to gain new converts to Christianity. A former gambler, drunkard, fighter, and swearing man who had no concept of the Gospel of Jesus or Christianity, Benjamin Abbot had been a converted Christian for 12 years by the time of meeting Richard Allen in the autumn of 1783. As you can see from Allen’s testimony of Abbott, Benjamin’s testimony and life were the key methods which Allen and the new converts were drawn to.

Allen would spend the remainder of 1784 in East and West Jersies. Close to year’s end, he would move to Pennsylvania.

From Allen’s autobiography:

”In the year 1784 I left East Jersey, and laboured in Pennsylvania. I walked until my feet became so sore and blistered the first day, that I scarcely could bear them to the ground. I found the people very humane and kind in Pennsylvania. I having but little money, I stopped at Caesar Water’s, at Radnor township, twelve miles from Philadelphia. I found him and his wife very kind and affectionate to me. In the evening they asked me if I would come and take tea with them; but after sitting awhile, my feet became so sore and painful that I could scarcely be able to put them to the floor. I told them that I would accept of their kind invitation, but my feet pained me so that I could not come to the table. They brought the table to me. Never was I more kindly received by strangers that I had never before seen, than by them. She bathed my feet with warm water and bran; the next morning my feet were better and free from pain. They asked me if I would preach for them. I preached for them the next evening. We had a glorious meeting. They invited me to stay till Sabbath day, and preach for them. I agreed to do so, and preached on Sabbath day to a large congregation of different persuasions, and my dear Lord was with me, and I believe there were many souls cut to the heart, and were added to the ministry. They insisted on me to stay longer with them. I stayed and laboured in Radnor several weeks. Many souls were awakened, and cried aloud to the Lord to have mercy upon them. I was frequently called upon by many inquiring what they should do to be saved. I appointed them to prayer and supplication at the throne of grace, and to make use of all manner of prayer, and pointed them to the invitation of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, who has said, “Come unto me, all ye that are weary and heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” Glory be to God! And now I know he was a God at hand and left not afar off. I preached my farewell sermon, and left these dear people. It was a time of visitation from above.”

According to the autobiography of Rev. Isaac James found in the annals of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference Historical Society, the Caesar Waters mentioned above was a slave owned by one of the members of the Continental Congress, Mr. Charles Humphreys. Mr. Humphreys was also a signer of the Declaration of Independence. According to Allen, these preaching engagements, which were largely the result of the requests of Caesar Waters and his kind wife, were to mostly white congregations: “There were but few coloured people in the neighbourhood–the most of my congregation was white.” Allen characterizes the effects of his preaching on his white and black skinned faithful resulting in deep mourning and lamentation. Evidently, the tears of repentance were abundant among the large congregations “of different persuasions.” Some proclaimed that Allen was surely a man of God, never hearing such preaching before: “We spent a greater part of the night in singing and prayer with the mourners.”

Of note is that Mr. Humphreys, who died in 1785, bequeathed to his servant, Caesar Waters, three acres of his Radnor Township property. Along with this gift of property, his freedom was also awarded to him in July of 1786.

More from Allen’s autobiography:

“I expected I should have had to walk, as I had done before; but Mr. Davis had a creature that he made a present to me; but I intended to pay him for his horse if ever I got able. My dear Lord was kind and gracious to me. Some years after I got into business, and thought myself able to pay for the horse. The horse was too light and small for me to travel on far. I traded it away with George Huftman for a blind horse, but larger. I found my friend Huftman very kind and affectionate to me, and his family also. I preached several times at Huftman’s meeting house to a large and numerous congregation.”

The George Huftman mentioned above is actually George Hoffman, founder of the Methodist Church in Chester County, Pennsylvania. According to the autobiography of Rev. James mentioned above, the church was known as Hoffman’s or Valley Meeting House and is the ancestor of Grove United Methodist Church, near Westchester. According to the journals of Francis Asbury, the Valley Meeting House in Chester County, Pennsylvania, was first called Goshen. This would be prior to his journal entry of May 6, 1773. It became Valley in 1774. The society there was formed in 1769 or 1770, with George Hoffman and Daniel Meredith as the leaders. More on this church can be found in, Reeves: Methodism in and around Chester.

In addition to the business transaction mentioned above, I find it unique that Allen would accept a blind horse to make his rounds. Perhaps he was assured that this was a good horse for an itinerant preacher having watched Asbury and his Biblical cavalry who made the same circuits over and over again on a weekly basis. It has been said that those horses never needed guidance to the next preaching spot- they knew the route just as well as the preachers did.

Baltimore Christmas Conference of 1784

Up to this point in history, the American Methodists were still connected to the Methodist of the British Isles. This was an awkward arrangement which at times led many of the American Colonists to view the American Methodists as traitors to the colonial cause in America. But after the surrender of the British to the American Colonists in 1783, a new arrangement was obviously needed.

Hosier and Asbury on horseback

That new arrangement came in December of 1784. John Wesley sent Dr. Thomas Coke from England to ordain Francis Asbury, and also to set the American Methodists up to be able to give the ordinances of baptism and communion. The transformational meeting needed for this new direction was set up for December of 1784 at the Lovely Lane Chapel in Baltimore, Maryland. Richard Allen attended- but he wasn’t the only African preacher present at this most important meeting. Francis Asbury’s long time fellow traveling preacher, Harry Hosier, attended as well. From this meeting, as many of Asbury’s itinerant preachers were sent off in many directions, Richard Allen was teamed up with one of Francis Asbury’s childhood friends from England, Richard Whatcoat.

Richard Allen and Francis Asbury and also with Richard Whatcoat

From Allen’s autobiography about Whatcoat and eventually, Francis Asbury:

“I found great strength in travelling with him (Whatcoat)–a father in Israel. In his advice he was fatherly and friendly. He was of a mild and serene disposition. My lot was cast in Baltimore, in a small meeting-house called Methodist Alley. I stopped at Richard Mould’s, and was sent to my lodgings, and lodged at Mr. McCannon’s. I had some happy meetings in Baltimore. I was introduced to Richard Russell, who was very kind and affectionate to me, and attended several meetings.”

Richard Whatcoat

“Rev. Bishop Asberry (Asbury) sent for me to meet him at Henry Gaff’s (Goughs). I did so. He told me he wished me to travel with him. He told me that in the slave countries, Carolina and other places, I must not intermix with the slaves, and I would frequently have to sleep in his carriage, and he would allow me my victuals and clothes. I told him I would not travel with him on these conditions. He asked me my reason. I told him if I was taken sick, who was to support me? And that I thought people ought to lay up something while they were able, to support themselves in time of sickness or old age. He said that was as much as he got, his victuals and clothes. I told him he would be taken care of, let his afflictions be as they were, or let him be taken sick where he would, he would be taken care of; but I doubted whether it would be the case with myself. He smiled, and told me he would give me from then until he returned from the eastward to make up my mind, which would be about three months. But I made up my mind that I would not accept of his proposals. Shortly after I left Hartford Circuit, and came to Pennsylvania, on Lancaster Circuit.”

It is interesting that Allen refused Asbury’s offer to travel. Asbury had already been traveling with another of African descent, Harry Hosier. But from Allen’s entry above, one can see the distinct personality differences between Allen and Hosier. Allen was a “go-getter,” if you will. One who was determined to make his way in life. Hosier, on the other hand, was always described as a content and quiet man- at least until he began to preach. Hosier’s preaching was considered by many to be a beautifully strong experience for the hearer. And by many accounts, he was one of the best preachers in America. Allen was a good preacher as well- maybe not at the level of Hosier and more at the level of Asbury, but his personality was much more outgoing than Hosier’s or Asbury’s. Allen was an enterprising young man, full of vigor and now the Holy Spirit. In fact, Hosier and Asbury seemed to be kindred spirits. Nonetheless, both Allen and Hosier were used mightily by God.

Allen’s strong-willed personality was on full display when you consider he would not take any income from the Methodist connection, in part because he liked to supply his own needs. His autobiography displays that there were times when, through his industry, he was able to supply more than he needed-like storing up for a future day, a rainy day if you will. See his entry below:

“Shortly after I left Hartford Circuit, and came to Pennsylvania, on Lancaster Circuit. I travelled several months on Lancaster Circuit with the Rev. Peter Morratte (Peter Moriarty) and Irie Ellis (Ira Ellis). They were very kind and affectionate to me in building me up; for I had many trials to pass through, and I received nothing from the Methodist connexion (connection). My usual method was, when I would get bare of clothes, to stop travelling and go to work, so that no man could say I was chargeable to the connexion (connection). My hands administered to my necessities. The autumn of 1785 I returned again to Radnor. I stopped at George Giger’s, a man of God, and went to work. His family were all kind and affectionate to me. I killed seven beefs, and supplied the neighbours with meat; got myself pretty well clad through my own industry–thank God–and preached occasionally. The elder in charge in Philadelphia frequently sent for me to come to the city.”

Richard Allen and St. George Methodist Church Philadelphia

That elder in Philadelphia was calling on Allen to preach at the famed St. George Methodist Church in Philadelphia. Again, from Allen’s autobiography:

“February, 1786, I came to Philadelphia. Preaching was given out for me at five o’clock in the morning at St. George’s Church. I strove to preach as well as I could, but it was a great cross to me; but the Lord was with me. We had a good time, and several souls were awakened, and were earnestly seeking redemption in the blood of Christ. I thought I would stop in Philadelphia a week or two. I preached at different places in the city. My labour was much blessed. I soon saw a large field open in seeking and instructing my African brethren, who had been a long forgotten people and few of them attended public worship.”

This is an interesting development in Allen’s preaching ministry. At first, Allen preached to whites at St. George, and eventually to his fellow Africans as well, some within the Methodist Cathedral as it was known, and some outdoors. At St. George’s, Allen was virtually the lead pastor to both blacks and whites. Allen continues:

“I preached in the commons, in Southwark, Northern Liberties, and wherever I could find an opening. I frequently preached twice a day, at 5 o’clock in the morning and in the evening, and it was not uncommon for me to preach from four to five times a day. I established prayer meetings; I raised a society in 1786 of forty-two members. I saw the necessity of erecting a place of worship for the coloured people. I proposed it to the most respectable people of colour in this city; but here I met with opposition. I had but three coloured brethren that united with me in erecting a place of worship–the Rev. Absalom Jones, William White, and Dorus Ginnings. These united with me as soon as it became public and known by the elder who was stationed in the city. The Rev. C– B– opposed the plan, and would not submit to any argument we could raise; but he was shortly removed from the charge. The Rev Mr. W. — took the charge, and the Rev L– G–. Mr. W– was much opposed to an African church, and used very degrading and insulting language to us, to try and prevent us from going on. We all belonging to St. George’s church–Rev. Absalom Jones, William White and Dorus Ginnings. We felt ourselves much cramped; but my dear Lord was with us, and we believed, if it was his will, the work would go on, and that we would be able to succeed in building the house of the Lord. We established prayer meetings and meetings of exhortation, and the Lord blessed our endeavours, and many souls were awakened; but the elder soon forbid us holding any such meetings; but we viewed the forlorn state of our coloured brethren, and that they were destitute of a place of worship. They were considered as a nuisance.”

Much has been written of this trying time at St. George Church. It is my opinion that some have missed some key points in this interaction between the white and black leaders, specifically the attempt by Allen to raise a church of those of African descent. For starters, many today have mistakenly applied a slightly distorted view of this period to all black and white church interaction during the colonial and early American periods. This is sad, especially when you consider the cordial exit and establishment of the African Methodist Zion Church in New York City. Yes, trying times would eventually surface in Baltimore and other locations, but New York City was different. Further scholarship may reveal a few other encouraging instances.

Looking at Allen’s own words from his autobiography above, you can see that the enterprising Richard Allen was planning, rather than scheming, for the future. This would be in line with his response to Francis Asbury when Asbury asked Allen to travel with him. Allen made it clear, he was thinking about his personal future. But not for selfish reasons. In Allen’s opinion, Asbury had a community which would support him in his old age. Allen did not. Perhaps this is one reason of several in which Allen would accept for leading an exit from St. George to establish a church of his fellow Africans. Perhaps too, Allen was thinking of his fellow Africans who would also need a support system in their old age.

Some of the white leadership mentioned by Allen may have taken it as scheming, but not all did. Subsequent evidence of friendly treatment by some key white St. George members reveals this. Going through Richard Whatcoat’s journal entries of his twenty-two years in America, we find several instances where Whatcoat, even after Allen’s departure from St. George, personally met with Allen and even dined at the Allen home on several occasions. One of Whatcoat’s entries mentions that Whatcoat even spent the night at the Allen home. Francis Asbury as well interacted with Allen on many occasions after the departure. Asbury actually is asked by Allen to give the dedication sermon for the new African Methodist Church Building. Whatcoat himself met many times with the Africans in Philadelphia.

It is also interesting that many of Allen’s fellow Africans did not want to leave St. George or start an African church. As Allen states above, many of the most respectable of his fellow Africans refused the idea. Allen uses the words, “I met with opposition.” His words that follow, “I had but three coloured brethren that united with me in erecting a place of worship,” seem to reveal his disappointment in their opposing of his community-building idea.

It is interesting that 1786 Philadelphia, much like 1786 New York City, was beginning to consider whether the cry of the American Colonists, that all men are created equal, was going to come to fruition. If you study some of the demographic details of the period, by the early 1790’s, the blacks south of Pennsylvania and New York were beginning to migrate north in mass numbers. Those who were free, on their own, many who were not free, under cover of night. This is undoubtedly on account that in contrast to the northern states, which were erecting laws forbidding slavery, the south was refusing to abandon the enslavement of Africans. History shows that this migration northward mostly affected the Methodist churches, on account of the fact that the Methodist movement from day one in America was sympathetic to the American Africans. Methodism of this period looked past the differences of ethnicity, wealth, and gender. This was the essence of all men being created equal. On the gender issue, many women enjoyed positions of leadership and teaching within early Methodism in America and in the British Isles. Women in leadership- another example of the essence of all men being created equal. The Methodist churches in the northern states couldn’t help but burst with African members.

It also seems that Allen took it on his own to separate his fellow blacks from the whites for “prayer meetings and meetings of exhortation.” Did all blacks agree with this? I don’t know. Allen’s words above seem to say that they did not all agree with Allen doing this. Did Allen mean anything sinister by this? It doesn’t seem so. Again, Allen is a thinker, an enterprising young man who quite possibly was thinking along the lines of an African community of support. He was deeply influenced by the truths of the Bible and perhaps the words of the Declaration of Independence. This may have seemed like a logical move for him and his fellow Africans. He does mention they were cramped for space. And more importantly, he does exhibit his love for his fellow Africans who, “few of them attended public worship.”

Could this move of meetings of only those of African descent be misunderstood by some of the white leaders? I think so. Many of their subsequent oppositions toward Allen reveal that they didn’t have a handle on what Allen was trying to achieve, especially when their actions turned toward removing Allen, who was virtually the lead pastor at St. George from St. George. They even went as far to attempt to completely remove Allen from the Methodist Episcopal Church. This is ironic when you consider Allen remained as a pastor and itinerant preacher at both St. George and the new African Church. It wasn’t until 1816, the year of Asbury’s death, that Allen left the Methodist Episcopal Church to become the Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. So for more than 25 years after the 1791 or 1792 incident, one resource puts it at 1787, (To Go and Serve the Desolate Sheep in America, The Diary/Journal of Bishop Richard Whatcoat 1789 to 1800, edited by Samuel J. Rogan, 2001), of escorting Allen’s fellow Africans and Absalom Jones out of St. George Church, Allen remained faithful to the Philadelphia Methodist Episcopal Church which looked down on him.

But consider this. If my research of this time period has shown me anything, it is that despite our misled, 21st-century opinions which tend to believe that all treatment of the Africans in colonial America, slave or free, was evil, there were free Africans who experienced it differently. Yes, many Africans of this period were brought here against their will, but some weren’t. Some were children of parents who survived the Atlantic crossing. Maybe these African children in America sadly did not experience the full-on approach of loving our neighbor as ourselves, but there were many instances of this actually occurring. And maybe when you consider that many Africans heard of or personally saw instances of Africans in Africa and Africans in America holding Africans as slaves, they were beginning to understand that sin is not a white’s-only byproduct of humanity. These glimpses of Africans in America being treated as neighbors to be loved had to prove hopeful to the Africans who experienced this edifying sense of community in colonial and early America, especially in light of the cries of the Declaration of Independence. Perhaps Allen was sensing this in a unique and focused way. A view that would lead him to start a Methodist Church of his fellow Africans in America. He did grow up in a household which entertained many of those men who were self-starters, enterprising men, who in the light of oppression, had such a focus to pen the words of the Declaration of Independence.

In addition to the above facts and opinions, Allen’s time in Pennsylvania would have opened his eyes to the many German churches. One such church led by Philip William Otterbein, was a regular preaching stop of Allen’s mentor and friend, Francis Asbury. Again, Allen had to be able to perceive the tight-knit community of these Germans. Allen must have wanted this same sense of community for his fellow Africans, especially as he and his brethren of color aged.

All this to say, more scholarship is needed.

Yes, eventually, with the white leadership at St. George being obviously unhappy with the developing sentiments of Allen and some of his fellow Africans, this did result in them banishing them from the pews and forcing them into the balconies which many of the Africans personally financed for the expanding church. Escorting Allen and his leaders of the future African Methodist Episcopal Church out of a morning service is further evidence that feelings had escalated. This inciting incident, unfortunate as it was, is undeniable. But as mentioned above, there are many more branches to this story than white prejudice. Perhaps white jealousy on account of the black solidarity in Philadelphia after the mistreatment. Many white leaders who were against the harsh treatment of the Africans looked down on their fellow white church members who failed to act as Jesus would have.

Absalom Jones

To cast all the white members of St. George as being against the blacks forming a community, or casting all the black members of St. George Church as being in agreement to form a separate community is disingenuous- casting each group, white or black, as monolithic. Allen’s own words affirm that this is an incorrect opinion. And it is a dishonor to men like Francis Asbury, Richard Allen, Richard Whatcoat, and others, white and black, who remained life-long friends. Consider this- in 1791, the African Methodist Episcopal Church officially organized. Three years later, with much help from several white members of St. George Church coupled with the tireless efforts of Richard Allen and other Africans, a spot for the church building was secured. Consider Allen’s own words about the escorting of Absalom Jones and company out of a worship service:

“By this time prayer was over, and we all went out of the church in a body, and they were no more plagued with us in the church. This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, in so much that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct. But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigor to get a house erected to worship God in. Seeing our forlorn and distressed situation, many of the hearts of our citizens were moved to urge us forward; notwithstanding we had subscribed largely towards finishing St. George’s Church, in building the gallery and laying new floors, and just as the house was made comfortable, we were turned out from enjoying the comforts of worshiping therein. We then hired a store room, and held worship by ourselves. Here we were pursued with threats of being disowned, and read publicly out of meeting if we did continue worship in the place we had hired; but we believed the Lord would be our friend. We got subscription papers out to raise money to build the house of the Lord. By this time we had waited on Dr. Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston, and told them of our distressing situation. We considered it a blessing that the Lord had put it into our hearts to wait upon those gentlemen. They pitied our situation, and subscribed largely towards the church, and were very friendly towards us, and advised us how to go on. We appointed Mr. Ralston our treasurer. Dr. Rush did much for us in public by his influence. I hope the name of Dr. Benjamin Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston will never be forgotten among us. They were the two first gentlemen who espoused the cause of the oppressed, and aided us in building the house of the Lord for the poor Africans to worship in. Here was the beginning and rise of the first African church in America.”

With a church location secured, who does Richard Allen ask to do the honor of preaching the opening sermon and giving the dedication prayer? As mentioned above, Allen asks Francis Asbury. Asbury gave the dedication sermon, and John Dickins gave the dedicating prayer, referencing Genesis Chapter 28 in the Old Testament. From Dickins’ prayer, the African Methodist Episcopal Church building in Philadelphia took its name. That name is Bethel. Mother Bethel, as it is known today. Perhaps that much needed scholarship I mention above will afford a much needed healing for America’s 21st-century Christian churches.

Richard Allen and the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic

In September of 1793, a public request was made to the African citizens of Philadelphia to help with the Yellow Fever Epidemic that had already killed many of Philadelphia’s white citizens. It was believed at that time in the epidemic that the Africans may have been unable to catch the deadly disease. This from an account of the Yellow Fever outbreak in much of the Caribbean. Unfortunately, the epidemic in Philadelphia did not behave like the epidemic in the Caribbean. Many of the Africans who helped with the suffering souls died from the Yellow Fever. By this time also, even Dr. Rush on account of losing many of his fellow physicians to the epidemic, was approaching the Africans of Philadelphia for help with bleeding the suffering.

The Africans of Philadelphia quickly responded to help. See Richard Allen’s and Absalom Jones’ own words on the times:

“Early in September, a solicitation appeared in the public papers, to the people of colour, to come forward and assist the distressed, perishing, and neglected sick; with a kind of assurance, that people of our colour were not liable to take the infection; upon which we and a few others met and consulted how to act on so truly alarming and melancholy an occasion. After some conversation, we found a freedom to go forth, confiding in him who can preserve in the midst of a burning fiery furnace. Sensible that it was our duty to do all the good we could to our suffering fellow mortals, we set out to see where we could be useful.”

“The first we visited was a man in Emsley’s Alley, who was dying, and his wife lay dead at the time in the house. There were none to assist but two poor helpless children. We administered what relief we could, and applied to the overseers of the poor to have the woman buried. We visited upwards of twenty families that day–they were scenes of woe indeed! The Lord was pleased to strengthen us, and remove all fear from us, and disposed our hearts to be as useful as possible.”

“In order the better to regulate our conduct, we called on the mayor next day, to consult with him how to proceed, so as to be most useful. The first object he recommended was a strict attention to the sick, and the procuring of nurses. This was attended to by Absalom Jones and William Gray; and in order that the distressed might know where to apply, the mayor advertised the public that upon application to them they would be supplied.”

“Soon after, the mortality increasing, the difficulty of getting a corpse taken away was such, that few were willing to do it, when offered great rewards. The coloured people were looked to. We then offered our services in the public papers, by advertising that we would remove the dead and procure nurses. Our services were the production of real sensibility; we sought not fee nor reward, until the increase of the disorder rendered our labour so arduous that we were not adequate to the service we had assumed.”

“The mortality increasing rapidly, obliged us to call in the assistance of five hundred men in the awful charge of interring the dead. They, with great reluctance, were prevailed upon to join us. It was very uncommon, at this time, to find any one that would go near, much more, handle, a sick or dead person.”

“When the sickness became general, and several of the physicians died, and most of the survivors were exhausted by sickness or fatigue, that good man, Dr. Rush, called us more immediately to attend upon the sick, knowing that we could both bleed. He told us that we could increase our utility by attending to his instructions, and accordingly directed us where to procure medicine duly prepared, with proper directions how to administer them, and at what stages of the disorder to bleed; and when we found ourselves incapable of judging what was proper to be done, to apply to him, and he would, if able, attend them himself, or send Edward Fisher, his pupil, which he often did; and Mr. Fisher manifested his humanity by an affectionate attention for their relief. This has been no small satisfaction to us; for we think that when a physician was not attainable, we have been the instruments in the hands of God, for saving the lives of some hundreds of our suffering fellow mortals.”

As you can see, the Africans of Philadelphia, led by Richard Allen, played a key role in nursing the sick, burying the dead, procuring medications, and doing medical procedures when called upon. Unfortunately, there were some who, after the town’s recovery from the epidemic, decided to slight the Africans. Rumors of charging too much for burials, stealing beds from dead families, and neglecting to help when called upon were hurled at the Africans of Philadelphia. Richard Allen and Absalom Jones refute these accusations and more in their editorial response in which the above citing is from. Allen and Jones admit that some Africans did commit some of these atrocities, but that an equal amount of those from European descent did the same. But most importantly, the published account was misleading. A disproportion of the blacks were represented as thieving. Aside from the much needed response’s stark nature, the account in great detail actually shows the extent that many of the Philadelphia citizens, black and white, had to go through in order to not only survive the epidemic, but also help their fellow man.

Some of the accounts by Allen and Jones are below:

“Perhaps it may be acceptable to the reader to know how we found the sick affected by the sickness. Our opportunities of hearing and seeing them have been very great. They were taken with a chill, a head-ache, a sick stomach, with pains in their limbs and back. This was the way the sickness in general began; but all were not affected alike. Some appeared but slightly affected with some of those symptoms. What confirmed us in the opinion of a person being smitten was the colour of their eyes. In some it raged more furiously than in others. Some have languished for seven and ten days, and appeared to get better the day, or some hours before they died, while others were cut off in one, two, or three days; but their complaints were similar. Some lost their reason, and raged with all the fury madness could produce, and died in strong convulsions; others retained their reason to the last, and seemed rather to fall asleep than die. We could not help remarking that the former were of strong passions, and the latter of a mild temper. Numbers died in a kind of dejection: they concluded they must go, (so the phrase for dying was,) and therefore in a kind of fixed, determined state of mind went off.”

“When the mortality came to its greatest stage, it was impossible to procure sufficient assistance; therefore many whose friends and relations had left them, died unseen and unassisted. We have found them in various situations–some lying on the floor, as bloody as if they had been dipped in it, without any appearance of their having had even a drink of water for their relief; others lying on a bed with their clothes on, as if they had come fatigued, and lain down to rest; some appeared as if they had fallen dead on the floor, from the position we found them in. Surely our task was hard; yet through mercy we were enabled to go on.”

“One thing we observed in several instances: when we were called, on the first appearance of the disorder, to bleed, the person frequently, on the opening of a vein, and before the operation was near over, felt a change for the better, and expressed a relief in their chief complaints; and we made it a practice to take more blood from them than is usual in other cases. These, in a general way, recovered; those who omitted bleeding any considerable time, after being taken by the sickness, rarely expressed any change they felt in the operation.”

“We feel a great satisfaction in believing that we have been useful to the sick, and thus publicly thank Doctor Benjamin Rush for enabling us to be so. We have bled upwards of eight hundred people, and do declare we have not received to the value of a dollar and a half therefor. We were willing to imitate the doctor’s benevolence, who, sick or well, kept his house open day and night, to give what assistance he could in this time of trouble.”

The more touching accounts given by Allen and Jones include orphaned children. See below:

“Several affecting instances occurred when we were engaged in burying the dead. We have been called to bury some, who, when we came, we found alone; at other places we found a parent dead, and none but little innocent babes to be seen, whose ignorance led them to think their parent was asleep; on account of their situation, and their little prattle, we have been so wounded, and our feelings so hurt, that we almost concluded to withdraw from our undertaking; but seeing others so backward, we still went on.”

“An affecting instance.–A woman died; we were sent for to bury her. On our going into the house, and taking the coffin in, a dear little innocent accosted us with–“mamma is asleep–don’t wake her!” but when she saw us put her into the coffin, the distress of the child was so great, that it almost overcame us. When she demanded why we put her mamma in the box, we did not know how to answer her, but committed her to the care of a neighbor, and left her with heavy hearts.”

“In other places where we have been to take the corpse of a parent, and have found a group of little ones alone, some of them in a measure capable of knowing their situation; their cries, and the innocent confusion of the little ones, seemed almost too much for human nature to bear.”

“We have picked up little children that were wandering they knew not where, (whose parents had been cut off,) and taken them to the orphan house; for at this time the dread that prevailed over people’s minds was so general, that it was a rare instance to see one neighbor visit another, and friends, when they met in the streets, were afraid of each other; much less would they admit into their houses the distressed orphan that had been where the sickness was. This extreme seemed in some instances to have the appearance of barbarity.”

On a different front were the misleading accusations of some who were bent on slighting the black community’s help in the epidemic. Despite the distorted accounts, Allen and Jones continued to aid in the effort, which helped to save many of the black and white citizens of Philadelphia.

In response to the published piece, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones offered a proverb which captured their sentiments toward the misleading accusations:

“We shall now conclude with the following proverb, which we think applicable to those of our colour, who exposed their lives in the late afflicting dispensation:

God and a soldier all men do adore

in time of war, and not before;

when the war is over, and all things righted,

God is forgotten, and the soldier slighted.”

In closing, Allen and Jones warmly offered their fellowship to the citizens of Philadelphia. See their closing below. Mayor Clarkson also offered his satisfaction of the help given by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. See his response after the closing by Jones and Allen:

“With an affectionate regard and esteem,

We are your friends,

ABSALOM JONES,

RICHARD ALLEN.

January 7th, 1794.”

Mayor Clarkson’s response to their efforts and the inaccurate portrayal of the majority of black citizens who helped with the epidemic is below:

“Having, during the prevalence of the late malignant disorder, had almost daily opportunities of seeing the conduct of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, and the people employed by them to bury the dead–I with cheerfulness give this testimony of my approbation of their proceedings, so far as they came under my notice. Their diligence, attention, and decency of deportment, afforded me, at the time, much satisfaction.

MATTHEW CLARKSON, Mayor.

Philadelphia, Jan. 23d, 1794.”

Richard Allen, Man of Integrity

As mentioned above, Richard Allen obtained his freedom from slavery at about the time of the end of the American Revolutionary War with England. He quickly began to travel on foot as an itinerant preacher. One story from the young man’s life-long example of integrity goes as follows. Somewhere in the vicinity of Wilmington, Delaware, the twenty-three year old Allen came across a large traveling trunk. Allen considered that the trunk may contain something valuable. Being the time that he was to leave for New York, Allen decided to place the trunk with a friend until his return back to Delaware.

Upon his return, Allen discovered that the trunk contained a large sum of French silver and gold. Immediately, Allen placed a public notice in several local newspapers. After many who came forward claiming ownership, the correct owner was located. The true owner was delighted and offered Allen twenty guineas as a reward. According to a Quaker hatter named Thomas Attmore who published a personal testimonial to Allen several years later, the honest Allen refused the offer of nearly one years’ wages, “from motives of conscience.”

After repeated attempts by the trunk’s owner to offer Allen lesser rewards, Allen eventually settled on a new suit, a plain new suit, in keeping with the founder of Methodism, John Wesley’s mandate that a Methodist preacher should dress plainly.

Many actions such as this by Allen caused Attmore to eventually write the testimonial toward Allen. It was in direct response to Allen’s consistent examples of integrity.