In the book, Black Country, it was at the 1766 Wesleyan conference that the first mention of Richard Boardman is made. At this conference in the northern portion of Great Britain in Yorkshire lies the largest county in England. Because of the shire’s large size, it is partitioned into four sections: north, south, east, and west. Easily one of the most picturesque settings in the entire nation, the county’s majestic rural landscape bespeaks the splendor of its Creator. Within the western slice of this northern paradise shines a town known for its successful woolen trade. This heavenly hamlet, nestled in a valley surrounded by verdant hills and bordering on the north side of the River Aire, is the community of Leeds.

The 1766 Leeds Conference finds Richard Boardman once again assigned to the York Circuit. This will be his third year on this arduous route. This is also the first time he will be separated from his friend and fellow traveling preacher, Joseph Pilmoor.

The York Circuit which Richard Boardman was once again assigned to incorporated the mountainous region known as the Dales. The rugged circuit in the Dales had 43 preaching stops and 980 members. It was here among the rocky cliffs and twisting valleys the Richard Boardman excelled as a preacher. So much so that when the American Colonies began to cry out for Wesleyan preachers, John Wesley sent Richard Boardman.

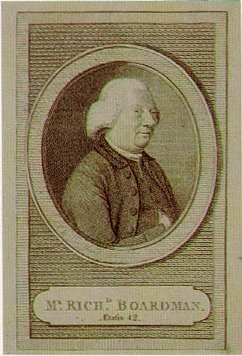

Richard Boardman American Missionary

It was an easy decision for John Wesley to send Richard Boardman as his first American missionary. For the past six years, the regular accounts of the fine ministry of Richard Boardman circled throughout the Wesleyan societies. In September of 1769, Richard Boardman embarked for the American Colonies. He will eventually serve in the colonies from October 20, 1769, to January 2, 1774. His work in America will thrive, but the younger newcomer named Francis Asbury will eventually become the leader of the American Methodist movement.

Richard Boardman Close Encounter with Death

Returning to the work of Richard Boardman in England, the following account of a close encounter with death will help to relate what these brave men of God faced on a regular basis. The account of Richard Boardman taking a break from his circuit in the Dales and heading for Wales to meet his dear friend, Joseph Pilmoor is from the book, Black Country:

“Approaching the riverside town of Flint, Richard glimpses the prominent structure on the edge of the estuary’s embankment, Flint Castle. Built in the thirteenth century when King Edward gained a foothold against the Welsh citizens, the royal building on the borderland is in dilapidated condition. Only the four prominent stone turrets and remaining portions of the site’s perimeter walls mark the ancient stronghold of the English King.

Searching the tiny town, Richard fails to locate Joseph. After several attempts at the local Methodist meeting house and the homes of its members, Richard realizes his only option is to cross the estuary. As he considers the expanse before him, the weather worsens as a light November snow begins to fall. The floating precipitation instinctively causes him to raise the collar of his jacket. He bundles himself more warmly and proceeds over the embankment at the edge of the estuary.

The River Dee estuary is a three-mile-wide mud flat, shaped much like an elongated basin. The numerous tiny shellfish that inhabit the nutrient-rich environment attract an abundant array of migrating birds escaping the arctic chill of the Northern European winter. The dried clumps of marsh grass that cover the sands provide natural cover for the migrating birds.

Richard hasn’t paid much attention, but at the hilltop, he realizes the snowfall has thickened. Blanketing the landscape and the atmosphere, the falling flakes have reduced visibility to a couple of yards. Richard contemplates the situation. In his mind, he knows he will find Joseph in Parkgate; an individual at the Methodist meeting house in Flint advised him of this. He also realizes the truth that this same individual offered: “Unless you ride fast, you will be in danger of being enclosed by the tide.” Enclosed by the tide. The words repeat, resounding like the bleating of the sheep in the Flintshire countryside. Richard prods his horse with his heels, hard.

The mare plods forward, down into the estuary, over and around numerous mounds of marsh grass. The low visibility increases the suspense as Richard begins to perspire with worry. Holding on with one hand, he raises the other to wipe the nervous sweat bead from his nose. Continuing downhill, Richard shades his eyes with his raised forearm. Squinting, he tries to look toward the west; in these conditions, this is an impossible task. He sighs in frustration, wishing he knew where the incoming tide is at this time. Richard suspects that in the distance, the waters are already emerging from the river. He pushes the horse to quicken the pace, the slow trot picking up to a moderate canter.

He leans back in the saddle as the decline to the estuary floor steepens. The falling snow is now wetting the entire length of his wool coat. The lumbering leaps of the mare as she negotiates the steep terrain bring a jarring pain to his back, but he does his best to aid the animal’s balance as they descend the treacherous slope.

At the bottom, the undesirable sound of horse hooves splashing in water alarms the itinerant. Sitting up completely, he pushes the creature to a gallop. The incoming water is now fetlock-deep to the mare. Richard is quickly soaked from the methodical pounding of four hooves beating the rising river. He covers his eyes for protection.

The snowfall thickens and visibility drops to within a foot. Richard’s gloved hands begin to chill from the splashing sea water. My window shall close shortly; Richard is aware of the obvious. The floor of the estuary rises chest-high in less than fifteen minutes. He must hurry to gain the opposite shoreline, or at least the rising portion of the estuary as it nears the town of Parkgate. The water is now nearing twelve inches in depth, the horse’s stride becoming more deliberate and more wetting to the rider.

The mare stumbles; Richard is tossed from the animal’s back. The water is up to his knees. Fearful of abandonment by his mount, he instinctively yells the horse’s name.

“Abbey!”

The mare nickers from only a few yards away. Marvelous creature! Richard is grateful that Abbey ceased her travel when her rider was lost. In the water, which now approaches mid-thigh, Richard treads toward his horse. Grasping the reins, he hops up and prods her to continue.

Father, I trust You are with me, Richard prays.

The snowfall slows, and the visibility begins to increase. Richard can make out the opposite shoreline ahead, nearly one thousand paces. The remaining half-mile causes him to look toward the west; his discovery alarms him. The water is well on its way. I doubt I shall arrive successfully. The water is now up to his ankles in the stirrups.

The mare can no longer run. She slogs through the flowing water as the dangerous current pushes the pair inland, toward the east.

From the opposite shoreline ahead, Richard notices the faint sound of two men yelling, attempting to gain his attention. They have it. In relief, he raises his hands and waves them frantically. The men race up the hill and over the crest, away from him.

Richard’s short-lived solace ends. I commend my soul to You, Lord. Richard embraces the possibility of the inevitable: death.

Back toward the west, the water continues it swirling onslaught. It is now just below Richard’s knees as he sits astride the horse. Abbey struggles to maintain any forward progress.

Looking in the direction of where the men had been, Richard spots them again. This time they are dragging a small wooden boat. At the edge of the estuary, the water is now weaving its way into the marsh grass at the embankment. The men push the boat into the approaching water. They hop in and shove off in Richard’s direction.

Richard eases his panic. The water occasionally rushes above the horse’s back; Richard can sense an occasional hop by Abbey as she experiences a slight buoyancy. He shifts his focus toward the men in the boat. They are paddling fast, but are still a couple of minutes away. Maintain balance, Abbey. Richard worries for the horse; he has never had to ride her in a full swim. Within moments, he faces a decision of staying atop Abbey or jumping in the water with her. He looks to the men. They are closer. However, the cold air and water have begun their undesirous effects; Richard begins to shake with cold.

Within a few yards, one of the men calls out,

“Surely, sir, God is with you.”

Richard nods an affirmative. The cold water is forcing his entire body to tighten. The men realize that the effects of the low temperatures are causing Richard to remain silent. They continue to paddle. The man with the grey hat offers again,

“Surely, sir, God is with you.”

“I trust He is.”

“I know He is. Here, hop into the boat. We shall swim the horse.”

At this, the men slide alongside Abbey and ease Richard into the boat. Grasping the reins, the man with the grey hat clicks his tongue against his teeth; Abbey responds to his audible prompt and swims alongside the tiny boat. The man holding the reins continues,

“I know that God is with you; last night I dreamed that I must go to the top of the hill. When I awoke, the dream made such an impression on my mind that I could not rest. I therefore went and called upon this man to accompany me.”

He points toward the man rowing the boat.

“When we came to the place of my dream, we saw nothing more than usual. However, I begged him to go with me to another hill at a small distance, and there we saw your distressed situation.”

Richard nods his affirmation, the chill in his body continuing to render him silent.

At the shoreline, several women join the rescuers as they deliver Richard. The women escort the itinerant into a home at the top of the hill. The two men secure the boat and escort Abbey to the barn adjacent to the home. Inside the barn, they feed the wet animal and give her a brisk rubdown.

Inside the home, Richard is relieved to sit next to a lit fireplace. The welcoming warmth aids in his recovery; the shaking of his body begins to slow. The women wrap the itinerant in warm blankets and offer several cups of steaming tea. As the two men return from the barn, one of the women remarks,

“Just last month we saw a gentleman in your very situation.”

Richard responds,

“I trust he was equally thankful for your aid.”

“Before we could hasten to his relief, he plunged into the sea—supposing, as we all concluded, that his horse would swim to the shore. But they both sank, and were drowned together.”