Women Preachers in History

After nearly two decades of the religious movement started by John Wesley in England several women, preachers emerged with an evidenced call to preach. Not only within their own hearts did they perceive such a calling, but also within the minds and hearts of those who knew them was there evidence that each of these women was given a special gift. There have been many women in the bible who have made a massive impact throughout history and still influencing women to this day. There are now even churches run by women who want to bring their congregation into the 21st century and advance the faith to as many people as possible. They can bring their churches on Holy Land tours (see here) as well as be the head of Christian organizations. Life truly has changed for the better.

Francis Asbury in his travels in England undoubtedly heard a handful of these women preachers. In Ashbourne, Derbyshire, Francis Asbury would have seen and heard first hand, Mrs. Dobinson, Sarah Crosby, Sarah Ryan and Mary Bosanquet (Fletcher), each had established leadership roles in the town of Derby. Also in London, these same women preachers, Sarah Crosby, Mary Bosanquet and Sarah Ryan, teamed up with other women preachers and leaders, would have had opportunity to share the Gospel in front of Francis Asbury during his two visits to the capital city. This experience, coupled with the acceptance of women in leadership as well as women preachers by John Wesley, influenced the opinion of Francis Asbury toward women preachers.

Who were these women preachers of the early Methodist movement in England? Equally important, were they the first to exhibit such a calling?

According to Dr. Paul Wesley Chilcote in his 1991 book, John Wesley and the Women Preachers of early Methodism, “Women have proclaimed the good news they discovered in Christ since the earliest periods of the Church’s history. The women preachers of early Methodism hardly represented a new phenomenon in the life of the Christian community…”

Saint Hilda one of the Earliest Women Preachers

What Dr. Paul Chilcote goes on to explain is that as early as the seventh century A.D. women have shared the good news of the Gospel and the freedoms found in Jesus. “As early as the seventh century women had attained positions of prominence in the infant communities of Anglo-Saxon Christianity. Once of the most outstanding of these early figures were Saint Hilda, abbess of Whitby, who in 659 founded a monastery for both men and women.” All who knew her called her “Mother.”

Other examples of women called to special roles in ministry include women in the Middle Ages who during a time of distrust of clerical leadership, stepped in to lead alongside men. Some of these also began to preach as in the example of the women preachers in the fourteenth-century Lollard movement.

During the Protestant Reformation led by Martin Luther, his insights gained from reading the Bible brought to light the emphasis placed upon the individual and the availability of direct communion with God. The reformation’s proclamation drawn from the scriptures that all are priests and called to the priesthood revived the desire of many women preachers to exercise their spiritual gifts one-hundred years before the work of John Wesley. From the launch of the reformation, the ideas of freedom of conscience, a believer’s right to freedom of thought and the spiritual equality of both men and women gained ground as they brought to life the logical conclusion that women as well as men had access to all of these life-changing values.

From the Reformation to the Puritan movement and eventually to the evangelical movement developed within the Anglican Church, an effort to simplify the worship and capture the spirit and focus of the early church were the natural result against the abuses which had long plagued the medieval church. During the Puritan movement when women once again began to experience the gift of prophesy, this evidenced practice allowed for women to expound for the benefit of the church. Although the Puritans clearly differentiated between Prophesying and Preaching, the small step from someone, women included, prophesying in a worship service and the possibility of them entering the pulpit to give a sermon eventually withered.

Further push in the direction of women preachers was experienced by the fact that un-ordained men were allowed to preach. It is precisely this fact, that un-ordained men were the majority of the leaders in the movement started by John Wesley– that Wesley permitted women preachers from as early as the 1760’s. All this to say that preaching by lay persons in England, men or women started in the early seventeenth-century by the Puritans in Holland. It is by this route that women preachers were once again allowed to preach in England. Despite these gains, the majority of the religious establishment as well as the majority of the non-conforming populace thought that the women preachers violated social and religious conventions.

The Quakers made the greatest strides in female liberation within the Christian church. Their efforts brought forth the rights of women to speak in public, participate in decision-making processes, and develop and use their spiritual gifts. The assertion of spiritual equality, privilege and responsibility by the Quakers from their inception was largely due to their core belief that all Christians possess the Light of Christ and that this illumination by the Holy Spirit allows that no individual can be disqualified from speaking as God’s Spirit gives them the ability to speak. So prominent were the women leaders in Quakerism that the rumor arose that the sect was exclusively female. In time, Quaker women preachers would begin to follow their call.

The first woman to accept these views was Baptist, Elizabeth Hooten. In 1648 she suffered being thrown in prison on four occasions for proclaiming her faith in public. The religious leadership in Boston forced Elizabeth Hooten to endure the barbaric punishment of the Cart and Whip Act of 1661. Other women of this period were at the same time proclaiming their faith in London, Dublin and the Quaker communities in Pennsylvania.

Where did the early Quakers gain the confidence to allow for women in positions of leadership in ministry? From the Bible in the passages from Acts 2:17-18, 21:9; 1 Corinthians 11:5; and Joel 2:28-29. Their opinion was that the Apostle Paul’s prohibition against women preachers was limited to local and temporary conditions. They also expressed that these limitations had long since passed away.

In his famous treatise of 1656, The Woman Learning in Silence, Quaker GeorgeFox proclaimed that if the spirit of Christ is in the women as well as the man, is not this Holy Spirit the same in either? He continued with the scriptural fact that this spirit is the same in the man as is in the women; there is no distinction.

Eventually, many of these early strides in England were lost on account of heretical practices of false women prophets who arrived on the scene in the early eighteenth-century. In one instance, a large group of French Protestants who were fleeing from persecution in France arrived in London, England where they began to prophesy the fall of the Roman church. Of these women preachers or prophets, two were extreme in their approach. Betty Gray and Pudding Pie Moll, brought upon themselves the full anger of a London mob as they gave their violent speeches against the Roman church, standing naked in the street. From this one group, several un-biblical and odd offshoots of Quakerism followed, leaving little acceptance of the women preachers.

John Wesley and Influence of Women Preachers

For John Wesley, the lessons learned from women in leadership began in the most unlikely place. Within the confines of the strict and orderly environment of his father’s ministry, the Epworth rectory, John Wesley gained his first brush with female leadership and women preaching through the example of his mother, Susana Wesley. The influence of Susana Wesley would go much further than influencing her children. Her efforts at leadership within the church touched the entire religious movement started by her son John Wesley. In fact, her efforts touched several continents affected by Wesleyan Methodism and clearly opened the door for John Wesley to eventually accept women preachers.

The daughter of the Puritan, Samuel Annesley, Susana Wesley was exposed first hand to the non-conforming teachings which separated the Puritans from a decaying Anglican Church. Dr. Paul Chilcote in his book calls Samuel Annesley, the “Saint Paul of Nonconformity.” Her father’s efforts brought to life a thirst for learning in his daughter Susana Wesley. She witnessed first-hand the numerous discussions that her father had with several of his “erudite colleagues.” In contemporary terms, Susana would be considered a liberated woman. This mostly because her father gained the freedoms found in the Holy Scriptures. These same liberating freedoms not only enlightened Susana Wesley, it was also these revolutionary ideals which eventually became the teachings of her own home. All this while she remained a member of the Anglican Church.

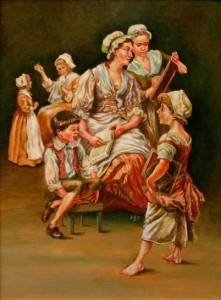

Susana Wesley and Women Preachers

Susana Wesley

Painting by

Richard G. Douglas

Key Influence of John Wesley’s Opinion of

Women Preachers

Susana Wesley is the forerunner of women preachers in John Wesley’s Methodist movement. This fact was not lost by John Wesley. In his discussions at the time of her death, he acknowledged that she in a unique way was a preacher and a priestess of the family. Even to those outside of the immediate family, the preaching efforts of Susana Wesley were well known. Even beyond the families of the Epworth rectory, her ministerial efforts spread throughout the town of Epworth. John Wesley’s opinion of the importance of laywomen in ministry was honed while watching his mother continuing family and society devotions for the Epworth rectory when his father was away on preaching engagements. The sense of responsibility for the spiritual health of her family and the families of the Epworth rectory were brought to life during the years of 1710 to 1712 when her husband was away for extended periods of time. Eventually, she began to conduct evening prayers for her family on Sundays. This effort grew to a point where the activities resembled a religious service, eventually becoming a form of public worship for the local people of Epworth. There were objections by some in the Anglican church, but the gatherings continued to grow.

Samuel Wesley Sr.

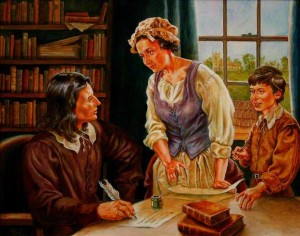

Susana Wesley

Samuel Wesley Jr.

Painting by

Richard G. Douglas

At one point, she was reaching out to several hundred people on a weekly basis. Opposition came from her husband’s assistant who mostly out of jealousy charged Susana Wesley with stealing the position of pastor of Epworth. The complaints made their way to her husband. He advised that she cease. However, Susana Wesley would not cease her efforts. Her response to her husband was that she noted that despite the fact that the curate’s services only reached about twenty people, her efforts were reaching nearly three-hundred people. Also, she informed of the transformed lives on account of these outreaches. Although she agreed with Samuel’s admonition against a woman usurping leadership in the church, she saw no other option for adequately handling the numerous needs among the Epworth faithful. Susana Wesley went as far as advising her husband to prepare a formal declaration forcing her to stop her efforts. She also advised that in light of such action, it would be Samuel, (her husband), and not Susana who would have to stand before the judgment seat and give an account for neglecting the opportunity to do well. Samuel Wesley chose the wiser path and allowed the gatherings of Susana Wesley to continue. The opinion that following God’s call regardless of your gender should never be stifled was solidified for John Wesley by the ministerial work of his mother, Susana Wesley.

The Early Church, the Moravian Church and Women Preachers

Early in his priesthood, John Wesley‘s initial leanings in the direction of women preachers took the form of deaconesses. He appointed deaconesses on the basis of two sources, the writings of the early church and the writings of the Moravian Church. The early church established through their Apostolic Constitutions, a clear description of the early church practice of appointing deaconesses to assist in the baptism of women. These female leaders also were to instruct in private children and women who were in preparation for baptism. The deaconesses were to also attend women in the church in need of restorative correction. Of the Moravian community, the Lutheran believers whom John Wesley met on his trip to Georgia, their unique approach to their religious community was the separation of the sexes. Men and women did not worship together. This opened the door for female leadership among the female faithful, women preachers if you will. Years later, John Wesley made a pilgrimage to the Moravian headquarters in Herrnhut where he saw the benefits of this creation of women leaders.

The Methodist Structure and Women Preachers

This practice of creating women leaders shows up within the Methodist structure of the gender-separated band and class meetings. It is within these community-building structures that the women are free to lead, speak, pray and preach. Early on in the movement, the prevalence of and demand on the female leadership in the various roles involved with the band and class meetings led those critical of the movement to comment that the Methodist women actually neglected their household and family responsibilities. Naturally, this was far from true, but it displays the extent of women involvement in the Methodist societies. This type of charge leveled against the Methodist faithful eventually brought about the derisive plays which portrayed both John Wesley and George Whitefield as running brothels full of women. It brought the mob when the public outcry was that Methodism utilized women preachers.

Despite the criticism, these Methodist women helped to forge forward the expansion of the Wesleyan movement. The women would invite the traveling preachers to their homes and a group of the local faithful would gather for exhortation. From these humble beginnings, prayer groups and eventually societies would form. When the itinerant preachers would depart, the women leaders, especially when no man would step in to lead, would take on the role of leadership. This soon led to the women leaders becoming temporary women preachers.

Paul Chilcote in his book, John Wesley and the Women Preachers of early Methodism, shares a startling fact in the early Methodist movement. “Another aspect of the involvement of women in the Wesleyan revival contributed greatly to the increased valuation of their presence and activity in the societies during this formative period and thereby paved the way to a greater acceptance of later developments. The women bore witness to the faith, and that not only in terms of their personal experience and the practical expression of the transforming gospel in their lives, but also in their courageous endurance of persecution, and for a limited number, martyrdom.” These Methodist women were not afraid to give their lives for their faith.

Again from Dr. Paul Chilcote’s book, “When a mob attempted to force its way into the home of Hannah Davenport (In Staffordshire, town of Leek) where she was protecting Thomas Hanby, she seized an axe, and taking her stand in the door-way, declared she would cut down the first who dared to approach. No one entered.”

The account is as follows: In the early years of the present century (18th) old Methodists at Leek used to tell how Thomas Hanby’s dinner at the inn was interrupted by the scared landlord, who begged him to leave lest the mob should pull down the house; how the preacher rode through the mob, who pelted him with stones and dirt, crying, ‘Kill him! Kill him!’ How on the next visit, a lawyer headed a mob even more furious, and the preacher, seeking refuge, in the house of Hannah Davenport, Jacob’s Alley, was defended by this woman, who seized an axe, and taking her stand in the doorway, declared that she would cut down the first who dared approach; how she swung the deadly weapon over the lawyer’s head, whereat he shouted, ‘stand back lads, for she will be as good as her word!’

Despite all the leadership roles taken by women in the early Methodist church, early in his leadership, Wesley was reluctant to allow women preachers in public. Much of this to protect himself and his revival movement from criticism from the Anglican Church. The last thing John Wesley wanted was to create a new church. He was loyal to the Anglican Church. But however hard he tried to limit the public’s and the church’s perception of the women leaders within the movement, the proliferation of women in leadership roles placed them on equal footing with their male counterparts. This soon became the public’s and the church’s biggest fear of Methodism.

Methodism’s ability to create leaders from within its structure went against English society where the working class and common folk were marginalized. A large portion of this working-class and common-folk was women. Within Methodism, these women no longer experienced the pains of disenfranchisement. This leveling-of-the-playing field experience as well as the empowerment inspired many to follow likewise. On a few rare occasions, women led a group of men in a class meeting consisting of both men and women. In these odd instances, there was no man spiritually mature enough to take the lead. Wesley’s views on such a situation follow: “As to the question you propose, if the leader himself desires it and the class be not unwilling, in that case there can be no objection to your meeting a class even of men. This is not properly assuming or exercising any authority over them. You do not act as a superior, but an equal; and it is an act of friendship and brotherly love.”

In another instance, a one John Hargreaves who enrolled himself in a class meeting in which the wife of an itinerant, Mrs. Hainsworth of Rakefort was the obvious leader. His comments are below: “…she stood spiritually and intellectually head and shoulders above every other member of the society… There is, however, such an incongruity in men’s meeting with female leaders, as must prevent it from coming into general practice; but there are some exceptional instances in which a female stands out in a Society so distinctly superior to all the rest of the members that the incongruity is reduced to a minimum.”

Grace Murray first of the Women Preachers

In the very beginnings of Methodism, Grace Murray is clearly a role model of the women preachers in the movement. As a member of the Foundry Church in London, her unending zeal allowed her to reach levels of accomplishment unheard of beforehand in the Methodist movement. As one of the early band leaders in 1742, Grace Murray, after losing her husband at sea, began her efforts as leader in the Newcastle society. John Wesley appointed her as leader of the entire society in Shropshire. Upon her appointment, she vigorously began her work dividing the bands into groups, women by themselves and the men also in their groups. She handled one-hundred people in classes. Each of these she met with twice each day, along with a band meeting each day of the week. In addition to these leadership responsibilities, she met with the sick and backslidden. If this wasn’t enough, she would also venture into the countryside to visit with additional, smaller societies. She would meet with the women in the day time and the entire society in the evenings. Shortly after this, Grace Murray was instructed by John Wesley to travel through several of the northern counties. There she met and regulated the female societies; later she did the same in Ireland. These arduous itinerant efforts brought out her evangelical leadership skills. Although she never attempted to preach, it was clear that she became by Wesley’s own admission, his “right hand.” In effect, Grace Murray was operating as an assistant pastor for the early Methodist movement.

Lay Preaching and Women Preachers

For John Wesley to go the next step in allowing women preachers, he would have to draw on his own theological experience. When he first struggled with field preaching for himself and his fellow Methodist preachers, his opinion was changed by the validation of the results of the transformed lives by the Holy Spirit. This validation by the Holy Spirit, directly affected his acceptance of lay preaching. In time, this validation convinced John Wesley of the same for the inclusion of women preachers.

The leveling principle so prevalent in the band and class meetings of early Methodism naturally morphed into the acceptance of lay preaching. John Wesley was an ordained Anglican priest. The men who experienced a spiritual transformation through his preaching of the word were not. In time, many of these born again individuals sensed God’s call to preach. John Wesley didn’t hesitate, especially in light of the evidenced work of the Holy Spirit in lives changed through the preaching of these lay preachers. His acceptance of the lay preachers was considered by many to be his biggest transgression from the Anglican discipline.

In A.M. Lyles’ 1960 book, Methodism Mocked: The Satiric Reaction to Methodism in the Eighteenth Century, one critic of Wesley’s ability to turn laymen into preachers clearly stated his objection: “The Methodist preacher came to an Anglican parish in the spirit, and with the language of a missionary going to the most ignorant heathens; and he asked the clergyman to lend him his pulpit, in order that he might instruct his parishioners for the first time in the true Gospel of Christ.”

John Wesley’s cautious acceptance of the lay preachers eventually becomes the model for him to accept women preachers in the 1760’s. And as expressed above, this acceptance of lay preachers brought scorn from the Anglican leadership. John Wesley, in his famous sermon #178, stated it best himself, these lay preachers were God’s “extraordinary messengers, raised up to provoke the ordinary ones to jealousy.” To Wesley, these men were unique because of their total commitment to Wesley’s Arminian theology and their steadfastness in submitting to the rules of the established Anglican Church. None of Methodism’s successful spread could have been accomplished without the use of lay preachers. Wesley could not have done the work on his own; the itinerant lay preachers helped to transform England.

How did Wesley know a man of faith was called to preach? In the 1746 conference in Bristol, guidelines were established. The three key requirements list below: 1: Do they know in whom they have believed? Have they the love of God in their hearts? Do they desire and seek nothing but God? And are they holy in all manner of conversation? 2: Have they Gifts (as well as Grace) for the work? Have they (in some tolerable degree) a clear sound understanding? Have they a right judgment in the things of God? Have they a just conception of the salvation by faith? And has God given them any degree of utterance? Do they speak justly, readily, clearly? 3: Have they success? Do they not only so speak as generally either to convince or affect the hearts? But have any received remission of sins by their preaching? A clear and lasting sense of the love of God? As long as these three marks undeniably concur in any, we allow him to be called of God to preach. These we receive as sufficient reasonable evidence that he is moved thereto by the Holy Ghost.

The evidence of grace, gifts and fruit became John Wesley’s test in determining who was called to preach. In time, the man possessing success in each of these as well as a desire to preach would be placed on trial for one year. After one year on trial, the lay preacher would be admitted into the full connection. At this time, further examination would occur by the conference. To John Wesley and his itinerant preachers, it was not enough to have a calling to preach, there had to be evidence of the success of this calling.

Priest or Prophet and Women Preachers

“By whom he would send.”

These words of John Wesley in his mind acknowledged that God was God and He had a right to choose whom he would empower with the life-giving message of the Gospel. Later in his life, he summarized this opinion in his sermon, “The Ministerial Office.” In this bold assertive, Wesley draws from the Old Testament: “In ancient times the office of a priest and that of a preacher were known to be entirely distinct… From Adam to Noah, it is allowed by all that the first-born in every family was of course the Priest in that family, by virtue of primogeniture (inheritance or succession by being first born). But this gave him no right to be a Preacher, or (in the scriptural language) a Prophet… For in this respect God always asserted his right to send by whom he would send.” In light of this, John Wesley perceived that his lay preachers were prophets and not priests. For women preachers, John Wesley came to the same conclusion. He eventually referred to women preachers as prophetesses.

John Wesley made one further distinction. He saw in the New Testament a difference between a pastor and an evangelist. The one often called a Bishop, and the other one who preaches the Word: “I do not find that ever the office of an Evangelist was the same with that of a Pastor, frequently called a Bishop… I believe these offices were considered as quite distinct from each other till the time of Constantine.” To John Wesley, the pastor took care of the flock, he gave the sacraments and was the leader of the flock. The evangelist or preacher was one who assisted the pastor by preaching. In light of this distinction, the lay preachers did not require ordination. To John Wesley, the lay preachers fell into the category of “by whom He would send.” In time, for John Wesley, this unique group eventually included women preachers.

Exhorter, The Local Preachers and Women Preachers

The position of Local Preacher within the Methodist movement was one who preached on the local level, in the local societies. They were usually employed in a secular job and received no pay from Methodist system. Their responsibility was to act as an assistant to the itinerant preachers, handling the local society until the traveling preacher returned. In this position, a large number of women participated.

This position was originally brought about by the imprisonment of some Methodist lay preachers when they were pressed into service for the Royal Navy in Cornwall. This extreme measure was an effort encouraged by the local magistrates who saw this as a mechanism to suppress the Wesleyan movement. At one point, almost no lay preachers remained in the country. Despite the missing lay preachers, the societies continued to flourish as members filled in on their own. Many of these willing members were women. Although the efforts of the exhorters was slightly less than the activities of a full-blown lay preacher, their call was still judged by the grace, gifts and fruits standard.

So what differentiated between the position of exhorter and the position of lay preacher? According to Margaret Batty in her M.A. thesis, The Contributions of Local Preachers to the Life of the Wesleyan Methodist Church until 1932, and to the Methodist Church after 1932 in England, “exhorting consisted of reproving sin, pleading with sinners to flee from wrath to come, describing his own experience in those matters and testifying to his present joy.” These exhorters eventually “found themselves as permanent substitutes for seldom-arriving traveling preachers, particularly in the more isolated areas. A common practice of reading one of Wesley’s sermons or other devotional material, interjecting comments or personal applications as particular situations merited.” Whether they knew it or not, the women who participated in this activity were receiving an experience that prepared them to become women preachers. This nearly invisible line between an exhorter and a preacher in many instances became impossible to detect when an on-fire speaker, man or woman, was delivering an impassioned word.

Building from these humble beginnings, the three principal means of speaking by the early Methodist women were, public prayer, public testimony and exhortation. The focus of each was to save souls.

Public Prayer and the Women Preachers

Mary Prangnell in Isle of Wight: “She became exceedingly desirous that others should partake of the same blessing, and this she diligently labored to promote, by forming prayer meetings in various parts of the neighborhood, and attending them at every opportunity without neglecting her duties as a wife and a mother.” (Dyson, Methodism in the Isle of Wight, pp. 134-138).

In Paul Chilcote’s book, “Sarah Moore, who received her first membership ticket in 1749 at eleven years of age and led the first class meeting at Hallam when only seventeen, was noted for walking ‘from her home in Sheffield to Bradwell to hold prayer-meetings in the house of Isabella Furness and Margaret Howe, of that High Peak village.”

Isabella Wilson of Yorkshire: “Hitherto, though urged to it, Miss Wilson had refrained from exercising herself publicly in the cause of religion, but hearing, from the late Mr. Percival, of the revival which had taken place in Yorkshire some years ago, in which it had pleased God particularly to own the prayer-meetings; and seeing her relations brought into Christian liberty, and the work prospering around her, from earnest supplication in private, she proceeded to pray more openly for such as were in distress of soul, and not in vain; the Lord often graciously answered for himself. Her mode of praying was not loud, yet fervent, and her faith remarkably strong in a present Saviour for a present salvation.”

“Some of the women, such as Sarah Crosby, were highly gifted in the art of prayer. On the occasion of her death, Frances Pawson recalled one of her unique qualities: ‘She used to begin prayer with the simplicity of a little child, and then rise to the language of a mother in Israel. Thus she prayed with the Spirit, and with understanding.'”

“Toward the close of the century no figure was so renowned for her exertions in public prayer as was Ann Cutler, affectionately known as ‘Praying Nanny.” “…her peculiar call from Heaven appears to have been chiefly the exercise of importunate believing prayer. Following her conversion she began to exercise her gifts in public and became more convinced about the authenticity of her calling:

She began to pray in meetings and several were awakened and brought to God. The effect of her labors were manifest. …Her manner and petitions were strange to numbers, as she prayed with great exertion of voice and for present blessings. She would frequently say, ‘I think I must pray. I cannot be happy unless I cry for sinners. I do not want any praise: I want nothing but souls to be brought to God. I am reproached by most. I cannot do it to be seen or heard of men. I see the world going to destruction, and I am burdened till I pour out my soul to God for them.'”

All the above: (John Pipe, Memoir of Miss Isabella Wilson, Methodist Magazine 31 (1808): 461-462).

“While her public prayers were generally very short, the extent and intensity of her personal devotional life was unparalleled. It was characterized by frequent and often lengthy periods of private prayer, as many as twelve to fourteen such times each day, in addition to usual nocturnal orisons. ‘For prayer,’ testified William Bramwell, ‘I never expect to see her equal again.'” (In William Bramwell’s, A Short Account of the Life and Death of Ann Cutler, 1827)

In London at the Foundry Church:

“The work of Sarah Peters in the London prisons during the early years of the revival affords an excellent example of the evangelistic application of prayer and its natural transformation into testimony and exhortation in such circumstances. Wesley observes that ‘it was her peculiar gift and her continual care, to seek and save that which was lost; to support the weak, to comfort the feeble-minded, to bring back what had been turned out of the way.’ The evangelistic urge of this Foundry Society band leader may be illustrated, moreover, by one of her own characteristic statements: ‘I think I am all spirit; I must be always moving, I cannot rest, day or night, any longer than I am gathering in souls to God.’ When Silas Told began his pioneering work among the condemned malefactors in London’s Newgate Prison, he found an able and willing assistant in Sarah. In October 1748, when religious services were organized for the inmates by these Methodists, Sarah proved indefatigable: Six or seven of those who were under sentence of death came. They sung a hymn, read a portion of scripture, and prayed. Their little audience were all in tears. Most of them appeared deeply convinced of their lost estate. From this time her labors were unwearied among them, praying with them and for them, night and day.”

Above from: (Some Account of Sarah Peters, Arminian Magazine 5 (1782): 128-136).

“She visited all of the prisoners in their cells, sometimes going alone, sometimes in the company of one or two others. She ‘exhorted them, prayed with them, and had the comfort of finding them every time more athirst for God than before. When John Lancaster one of the first converts, entered the press-yard to be executed, he saw Sarah, stepped to her, kissed her, and earnestly said, I am going to paradise today. And you will follow me soon.’ His prophecy was fulfilled, when two weeks later, she died from the ‘prison fever,’ contracted as a result of her labors. In these types of exercises the thin line between prayer and exhortation, or even scriptural exposition and preaching, often became blurred.”

Public Testimony and the Women Preachers

From Dr. Paul Chilcote’s book, John Wesley and the Women Preachers of early Methodism: “The necessity of religious self-expression within the small groups of early Methodism served to train an articulate laity and became an important factor in the spread of the gospel through both male and female instrumentality.”

The sharing of personal testimonies usually occurred after a worship service. In Wales, after preaching at Llansaintffraid, Wesley records that one of the women,

“Could not refrain from declaring before them all what God had done for her soul. And the words which came from the heart went to the heart. I scarce ever heard such a preacher before. All were in tears round about her, high and low; for there was no resisting the Spirit by which she spoke.”

There were other opportunities for the faithful to share their testimonies. “The early morning preaching service, the love feast the watch night service, and the covenant service all became distinctive features of the Methodist revival.” (Frank Baker, Methodism and the Love Feast). It was in the love feast where the best chance for women to speak publicly of their personal faith experiences existed.

The first love feast was held by the women of the Bristol Society on April 15, 1739. This special gathering was a natural extension of the class meetings. The class would come together to eat, drink and share of their experiences together. Although the symbolic breaking of bread together had its place, it was the personal testimonies which were the highlight of these agape gatherings.

The value for future women preachers is this setting was that the women who felt called to share were given a very public platform to do so.

Many of the early women preachers share a common experience of apprehensiveness to the call. Eventually, this reservation would subside and lead them to speak in public. The account of a Jane Cooper can “be multiplied many times over with regard to the experience of the early Wesleyan women. The breakthrough for Jane Cooper came on January 15, 1762:

“Went to London on Friday to the meeting. Mr. Md. Desired any to speak who had not before declared the goodness of God. I was convinced I ought to speak but feared I should bring a reproach upon the cause by my foolishness was tempted to think I should fall down in a fit if I began and that I knew not how to order my speak aright. But the Lord said ‘take no thought how or what you shall speak for in that hour it shall be given you…’

I felt an awful sense of God while speaking and sat down with emotion that spoke to my heart well done good and faithful servant. My soul was so well satisfied with the approbation of ecstasy. I neither wished nor feared what man thought of me. I only prayed they might receive the truth in the love of it lest their souls should suffer loss. I am content to be vile let God be glorified and it sufficeth.” (Sarah Crosby MS Letterbook, 1760-1774).

Exhortation and the Women Preachers

Although exhortation is like preaching, the definition of exhorting by John Wesley emphasized that exhortation was mostly about reproving one of their sinful actions. The act by definition fell short of sanctioning women preachers. No text was expounded upon, only what was spoken was to create a reaction or response in the faithful who were in need of correction.

A unique purpose of exhortation occurred on someone’s deathbed where they would plead with their loved ones to turn to the Lord. Consider the deathbed exhortation of Sally Colston in her earnest plea to the young people who came to see her for the last time: “Turn to the Lord in the time of your youth. Trust in the Lord with all your hearts.”

Exhortation is the obvious progression of public prayer and testimony. One early example was a young lady from Yorkshire. Ann Thompson, after her conversion by women preachers, began to pray in prayer meetings. Soon, she began to bring a word of exhortation. With the success of her efforts, she continued her efforts of public exhortation. Many were her joys as she experienced many who gained salvation through her sharing of the Gospel.

“Penelope Newman, a bookseller from Cheltenham who later became a renowned woman preacher, began to exhort in prayer meetings soon after she united with the Methodists. Through these activities she was instrumental in the conversion of the man she would marry, Jonathan Coussins, who thereafter became one of Wesley’s noted itinerants.” (By W.A. Green, “Jonathan and Penelope Coussins,” Wesley Historical Society Proceedings 34, 3 September 1963, pp. 58-60, and Methodist Magazine 29 (1806): 290-292, 296, 344).

“By means of such exertions, Methodism was founded in Barnard Castle in about 1747 by Catherine Graves. After traveling with George Whitefield in Scotland, she returned to the Dales, instituted a prayer meeting in that market town, became the leader of a class, and exhorted the small assemblies when they gathered together.” http://americanduchess.blogspot.com/2013/02/18th-century-pattens-for-shoes.html) (Harold Beadle, Methodism in Barnard Castle and Upper Teesdale before 1800, WHS Proceedings, Northeast Branch 21 March 1974 pp4-8).

For the most part, exhortations followed an itinerant’s preaching. Consider Mary Holder. In a correspondence to Zechariah Taft, Mary shared about her exhortation: “My method, as you know, was to give a word of exhortation after my dear husband had finished his sermon, or to pray, as I felt led by the spirit of God: and I must say, the Lord has owned and blessed my feeble efforts, to the spiritual profit of some precious souls.”

As successful as these early women preachers or exhorters were, the efforts were plagued with internal struggle. Consider the words of Judith Land of Norfolk as she fought to bring together her call in the face of social and religious opposition:

“Feeling an increasing love for perishing sinners, and an earnest desire for their salvation, she ventured in public to give a word of exhortation, which the Lord owned with his blessing. She began to feel this more and more her duty: indeed the salvation of her own soul seemed closely connected with her striving to save the souls of others; she became greatly alarmed at this, especially when she considered her want of judgment and ability; on this ground she endeavored to excuse herself, and stifled those convictions, until the anguish of her soul became intolerable… she had no peace until she consented to exhort sinners to repent and turn to God: so as soon as she obeyed God in this, her peace returned. She is never so happy as when exercising in these labors of love, knowing that this is the will of God concerning her. Hitherto the Lord has owned her labors, hereby testifying that she is not deceived.”

One Alice Cross of Booth-Bank in Cheshire came the closest to preaching by the early women exhorters. The once loud and unconventional woman, introduced Methodism to Booth-Bank in 1744. Her practice of inviting itinerants to her home to preach brought about the erection of a pulpit in her home. On occasion, an itinerant didn’t show, or when he did, his preaching was substandard, Alice would walk to the front of the room, stand next to the pulpit with her face to the wall and exhort. In time her efforts resembled preaching, despite the fact that she was facing perpendicular to her listening audience. One thing was for sure, Alice preached but never entered the pulpit!

John Wesley’s Change of heart toward Women Preachers

In the remainder of the 1740’s and the early 1750’s, John Wesley did not fully accept women preachers. There was public prayer, public testimony and public exhorting, but not a full-fledged nod toward the sanctioning of women preachers. However, in 1755, the conference document which John Wesley presented seemed to make provision for women preachers in exceptional cases. In the document, John Wesley differentiates between the authority to preach and the authority to administer the sacraments. Again, for this distinction, John Wesley appeals to the early church:

“Evangelists and deacons preached. Yea, and women when under extraordinary inspiration. Then both their sons and their daughters prophesied, although in ordinary cases it was not permitted to ‘a woman to speak in the church.” (In Wesley’s translation of 1 Corinthians 14:35, Wesley correctly alters the ‘women’ of the Authorized Version to ‘woman’.

So who was the first woman to receive this authorization toward women preachers? Sarah Crosby was the first to receive John Wesley’s blessing in this endeavor.

Having the privilege to hear both George Whitefield and John Wesley preach in London, Sarah Crosby in 1750 joined the Foundry Church. Within two years, she became class leader. Within five years, she found herself abandoned by her husband. At this point in her life, she became friends with Mary Bosanquet. This friendship would become a significant relationship in early Methodism, the two eventually becoming women preachers.

From her early childhood, Sarah experienced strong religious impressions. Her involvement with the Foundry society brought to life a deep urge to exhort others to repentance and faith. Consider her words:

“From the love I felt to those I knew to be equally fallen from original righteousness with myself, I often desired to be instrumental in turning them to God, and never had a moment’s peace ay longer than I endeavored to aim at this wherever I came.” (Arminian Magazine 29 (1806): 466-473. Also other references in this Arm. 29, 564, 420-421).

As time went on, her spiritual growth in the faith led her step by step to a point where her public testimony began to resemble public preaching. Her call to preach came during a time of spiritual grasping of God’s grace I her life. She recounts the experience to John Wesley in a letter: “I felt my soul as a vessel emptied, but not filled. Day and night I was amazed at the blessed change my soul experienced; but I said nothing to any one, because I was not, as yet, sure what the Lord had done for me; though I had always promised, if the Lord would but fully save me, I would declare his goodness although I believed it would expose me to various exercises, both from ministers and people.”

In the spring of 1760, Sarah Crosby experienced the completeness of her salvation. It was at this point that she felt led to preach. Having the year before led a Mrs. Dobinson to participate in her class meeting at the Foundry Church, Mrs. Dobinson soon joined Sarah Crosby and Mary Bosanquet in conversation about evangelical efforts in Derby. 18 months later, the trio set out for Derby. “At the commencement of 1761, this zealous new Methodist and her husband moved from London to Derby with the express intention of forming a Methodist society there. In this enterprise, they were supported through the presence and assistance of Mrs. Crosby. (G. Arthur Fletcher, Derby- The old Chapel in St. Michael’s Lane, W.H.S. Proceedings, 15, 4(December 1925): 109-110). This project was evidently planned over the course of several months as a letter from Mrs. Crosby to a Sarah Moor (of Sheffield?), dated September 1760, London, would indicate: “I shall set out for Derby about a month hence, but cannot tell you where to direct to. Perhaps you will see Mr. Hampson again first, who may be able to inform you, or bring me a letter.” Hampson was the itinerant who was eventually appointed to that circuit). Not only did this venture lead to the establishment of a society, but it marks the beginning of the work of women preachers in Methodism as well.”

February 1, 1761, there were twenty-seven people attended the first class meeting that Sunday evening in Derby. Sarah Crosby gives an account of the events that followed the week after: “Sunday, 8th: This day my mind has been calmly stayed on God. In the evening I expected to meet about thirty persons in class; but to my great surprise there came near two hundred. I found an awful, loving sense of the Lord’s presence, and much love to the people; but was much affected both in body and mind. I was not sure whether it was right for me to exhort in so public a manner, and yet I saw it impracticable to meet all these people by way of speaking particularly to each individual. I, therefore, gave out a hymn, and prayed, and told them part of what the Lord had done for myself, persuading them to flee from al sin.” (Arm. Mag. 29, 1806, pp. 518, this experience is the same as Susanna Wesley’s Epworth experiences).

Sarah immediately wrote Wesley for advice about the event. John Wesley does not come across as being worried. Consider his answer which was not sent nearly three days after he received news from Sarah: While John Wesley was penning his response, Sarah Crosby addressed the Derby faithful again on Friday, February 13. In this large gathering Sarah sensed confirmation that she was doing the right thing. Consider her own words:

“In the evening I exhorted near two hundred people to forsake their sins, and showed them the willingness of Christ to save: They flock as doves to the window, tho’ as yet we have no preacher. Surely, Lord, thou hast much people in this place! My soul was much comforted in speaking to the people, as my Lord has removed all my scruples respecting the propriety of my acting thus publicly.”

Wesley wrote back:

“London, February 14, 1761 My Dear Sister, Miss Bosanquet gave me yours of Wednesday night. Hitherto, I think you have not gone too far. You could not well do less. I apprehend all you can do more is, when you meet again, to tell them simply, ‘You lay me under a great difficulty. The Methodists do not allow of women preachers: (because of Wesley’s conviction to not separate from the Anglican Church),neither do I take upon me any such character. But I will just nakedly tell you what is in my heart.’ This will in a great measure obviate the grand objection and prepare for J. Hampson’s coming. I do not see that you have broken any law. Go on calmly and steadily. If you have time, you may read to them the Notes on any chapter before you speak a few words, or one of the most awakening sermons, as other women have done long ago.” (Wesley Letters 4:133. In actuality, another preacher, a Mr. G—h came to her relief rather than Mr. J. Hampson.)

John Wesley’s approval of Sarah’s efforts marks his acceptance of women preachers.

Methodist Women Preachers 1761 to 1763

In the spring of 1761, Sarah Crosby was making her way to London from Derby. In London at this time, a revival was taking place among the Wesleyan societies at the Foundry Church and Whitefield’s Chapel. Here are her words in a letter dated January 28, 1763;

“I have been 5 months at Canterbury, which has been much for my own good, and the good of many. There has been a great revival, and quickening among the people. When I have an opportunity, I will send you the copy of the account, Mr. Wesley desired me write him.” (Sarah Crosby to Mr. Oddie, at the New Room, in the Horse Fair, London, January 28, 1763, Methodist Archives Rylands Library, Manchester, UK)

Sarah Crosby’s return to London opened the door for her to reestablish her friendship with Mary Bosanquet and Sarah Ryan. Each of these in time would become Methodist women preachers. In March of 1763, the wealthy Mary Bosanquet and the domestic servant Sarah Ryan teamed up with Sarah Crosby to begin an outreach to the destitute of London at Leytonstone. Their goal was to establish an orphanage and school along the lines of Wesley’s Kingswood school in Bristol. Their focus, those without family and friends, the destitute children, some of which were found “naked and full of vermin.” (Paul Chilcote’s book). Over the next five years, thirty-five children and thirty-four adults were taken in. For more on this, go to the Sarah Crosby character page.

The “Extraordinary Call,” and Women Preachers

“During the decade of the 1770’s John Wesley became increasingly aware of the increasing push in the direction of women preachers. By now, Francis Asbury had departed for America. However, the leanings of John Wesley and his opinion of women preachers did not escape Asbury in America. Wesley’s unsuccessful attempts to reconcile with the Anglican structure began to push him in the direction of preserving the Methodist movement. Although he wished to remain subject to the Church of England, the church’s hierarchy were not so fond of Wesley and his Methodism.

According to Dr. Paul Chilcote in his book, John Wesley and the Women Preachers of early Methodism, “The transformation of Wesley’s attitude toward the women preachers during this critical period, and the consequent expansion of their labors and influence within the Methodist societies, cannot be fully understood apart from the context of these general developments. Decreased anxiety concerning the stability of his bond with the Church of England made it easier for Wesley to countenance the development of additional irregularities as long as they promoted the cause of evangelical Christianity.”

“The case of Sarah Crosby, as we have seen, clearly demonstrates the cautious progression of Wesley’s thinking in this regard. In 1761, he discreetly approved her actions in Derby and admonished her to speak in public about her Christian experience or to read edifying literature to her assemblies as his mother had done at Epworth. In 1769, he agreed that she might even deliver short exhortations, carefully avoiding what appeared to be preaching by frequently interrupting her discourse and never taking a text. During the years that immediately followed, these developments came to a head, however, and it became increasingly clear to Wesley that he must accept an occasional woman preacher by virtue of an ‘Extraordinary Call.'”

When did this change in Wesley’s opinion toward women preachers change is hard to know. A leading cause may have been the outreach of Sarah Crosby, Mary Bosanquet, Sarah Ryan and several other extraordinary women of faith associated with the London work. In the summer of 1771, Mary Bosanquet wrote John Wesley. In the correspondence, she pleads her case that from her looking through the Bible, women on occasion, experienced a call from God to preach, “in extraordinary situations.”

Employing lines of argumentation similar to those which characterized Margaret Fell’s Women’s Speaking Justified nearly a century before, Miss Bosanquet carefully considers the classic statements of Saint Paul in 1 Timothy 2 and 1st Corinthians 14 and addresses six objections that had been raised concerning their specific activities.”

Again from Paul Chilcote’s book, “Her first conclusion is that the so-called prohibitive passages refer to specific situations in which certain women were meddling with church discipline and government and do not apply, therefore, either to women in general or preaching in particular. Furthermore, a literal interpretation of these scriptural texts would contradict the apostle’s admonitions concerning the necessity of women prophesying with their heads covered, in 1st Corinthians 11:5. In her view, the objection that the speaking of women should be limited to times of a ‘peculiar impulse’ placed too severe a limitation upon the gracious activity of God. The Almighty could as easily inspire a servant to speak ‘two or three times in a week, or day’ as ‘two or three times in her life.'”

Mary Bosanquet

One of the Early

Methodist

Women Preachers

Mary Bosanquet in her defense of women preachers focused also on women in the Bible who were said to possess godliness. Her examples were Mar, the woman of Samaria, the handmaid of 2nd Samuel 20, and Deborah. Each of these, Mary states, were characterized as pure and humble, and publicly declaring a message from God. Mary replies to those who object:

“If I did not believe so, I would not act in an extraordinary manner. I praise my God, I feel him very near, and I prove his faithfulness every day.”

Wesley’s reply reveals his changed heart toward women preachers:

“My dear sister, I think the strength of the cause rests there, on your having an Extraordinary Call. So, I am persuaded, has every one of our Lay Preachers: otherwise, I could not countenance his preaching at all. It is plain to me that the whole work of God termed Methodism is an extraordinary dispensation of His Providence. Therefore, I do not wonder if several things occur therein which do not fall under ordinary rules of discipline. St. Paul’s ordinary rule was, ‘I permit not a woman to speak in the congregation ‘yet in extraordinary cases he made a few exceptions; at Corinth, in particular.'” Londonderry June 13, 1771 (The Bristol Conference in 1771, the one which sent Francis Asbury to America, was on August 6th to August 9th).

Following this reply of John Wesley to Mary Bosanquet, the subsequent decade, the 1770’s, saw an increase in the influence of women preachers. As a result, their efforts touched the entire British Nation.