Bishop Francis Asbury Bicentennial Podcast

Bishop Francis Asbury Chaise Drawing by

Tyler Fegley

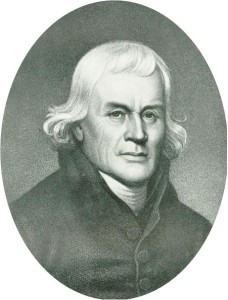

March 31, 2016, marks the bicentennial date of the passing of Bishop Francis Asbury. Fitting with his 45-year ministry in America is that he finishes his days on a lonely back road, virtually in the middle of nowhere, in the state of Virginia.

The dramatic audio piece detailing the last days of Bishop Francis Asbury is complete! Below is the dramatic telling of the last days of his life, recreated in a moving audio production.

The audio version of, My Work Is Done, is a 40-minute drama complete with rich dialogue, cinematic background music, and a dramatic portrayal of Bishop Francis Asbury and his close friends who give comfort and aid to the ailing bishop in his last days. The closing of the piece includes an interesting anecdote featuring the earthly items left behind by the last will and testament of Bishop Francis Asbury.

Click on the podcast below and enjoy a step back in time, to the beginning of the 19th-century and the end of a magnificent life lived to the glory of God.

My Work is Done: The Last Days of Bishop Francis Asbury

A dramatic telling of the last days of Bishop Francis Asbury

Sitting upright in the tightly wound bed, the thin, ailing man surprises the others in the room when he ekes out a smile. It is a welcomed gesture, a pleasure inspiring the man standing at the edge of the oak bed to gently bend to one knee as he places his hand on top of the ailing man’s hand.

“It has been some time, Francis. Your smile elevates each of us.”

Francis leans slightly forward. “Does it remain the month of March, the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and sixteen?”

Looking to the tired traveler, the gentle friend replies, “It is. You’ve been here for nearly one week; it is now the twenty-fourth of March.”

With a small nod, Francis acknowledges the revelation. “I must continue to be in haste… Baltimore awaits.”

Francis clears his throat, the strained rasp making it clear that this is an arduous task. An adjacent window’s feeble offering of sunlight begins to sink upon the pale, creased face of the aged itinerant, the deep furrows bespeaking nearly five decades of travel outdoors. The exposing beam furthers its cruelty as it discloses the sparse frame of a once vibrant and hearty man. The bones of this dear servant appear to cut through the blotchy skin of his formerly vigorous hands.

The man who lovingly places his hand onto the frail hand of Francis Asbury is the Reverend Archibald Foster, ordained by Asbury as a Methodist itinerant 27 years before. The other man in the room, also visibly lifted by Francis’s smile, is also a preacher. In fact, he is a bishop of what remains of the colonial American Anglican Church, the Bishop Richard Channing Moore. Bishop Moore is rector of the Monumental Church in Richmond, Virginia. Since the end of the war with England, Bishop Moore has done his best to revitalize a church devastated by the evacuation of its English preachers during the revolutionary struggle.

These two men can hardly believe that Francis is attempting to travel. Looking to each other, their faces express the same doubt: He longs to make the conference in Baltimore? Impossible…

Looking to his two companions, Francis draws a deep, elongated breath to gain the strength needed to speak. “I must pray.”

The men nod their agreement and bow their heads. Francis begins, “O Father, once again I place myself before You. It pleases me so…”

He pauses.

The pause is far from uncomfortable. The unexpected silence escorts into the dry and pallid room the welcomed chimes of dozens of spring birds as they lightly dance between boxwood and buttonwillow bushes. Their proclamations seem to indicate that any day now they will make their way further northward—a sentiment which mirrors that of the failing Francis. It is his strong desire to attend the General Conference in Baltimore on the second day of May.

After nearly a minute of silence, Francis continues his prayer. “Do you tire of my simple exchanges?”

Another pause.

“Thank you; I am pleased that You do not. As You have so peaceably shared, my journey draws to a close. My work is nearly done…”

“Yes, it pleases me so to know that eternity draws near…”

“I will.”

Opening his eyes, Francis removes his hand from beneath Reverend Foster’s hand, noticing how the reverend’s robust appendage stands in sharp contrast to his own waning extremity. Yes, my work is nearly done… Francis’s thought silently attests that he freely accepts God’s will.

Reverend Foster comments, “Francis, you pray as if you are talking face to face with God.”

With the slight turn of his head and the tilt of his smile still exhibiting one last ounce of mischief, Francis replies, “Despite my severe affliction, I soon shall enjoy such sweet occasion.”

The reverend smiles, a slight chuckle accompanying his observation of the ailing Francis. “That tipped smile—I shall miss it immensely.”

“Ah!”

Francis’s sudden exclamation indicates that he is in pain.

Again: “Ah!”

The last shout is followed by a long, low moan. Hunched over, Francis’s body clenches as it wrestles with wracking pain.

The men in the room have by now grown grimly accustomed to Francis’s outbursts of pain. Reverend Foster gently places his hand onto Francis’s aching shoulders. After nearly a full minute of guttural groaning, Francis leans back.

Without notice he shouts, “Hallelujah! Hallelujah!” Turning toward Reverend Foster, he explains, “The severest and the sweetest affliction! I am a perpetual martyr, walking in living death.”

No one responds. Although they are glad Francis’s jubilant cries indicate the passing of the pain, they silently ache for their friend who is daily closer to departing this life for eternity.

Sensing their sorrow, Francis offers, “My flesh has wasted away. I am ghastly. The General Conference wishes me to stop and sit for a portrait. If they want my likeness, now they may have it.”

This time the men cannot help but respond. Both let out a short laugh. Reverend Foster recalls his earlier comment about Asbury’s sense of wit. “Just as I was saying…” All in the room grin in appreciation of Francis’s courage.

A light knock on the bedroom door is followed by the measured opening of the oak slab. The slight creak of the wooden hinges invites the three men to turn their eyes toward the young man who enters. With a grateful nod the new arrival announces, “Bishop Asbury, it is a welcomed surprise to see you awake. We have worried tremendously for your well-being.”

Francis responds, “Yes, John, it is a most welcome blessing. Please, prepare my chaise; I would like to preach this evening.”

“Bishop Asbury, you are far from being able to preach.”

“Yes, Bishop Asbury—as young John is warning, you should rest a day.” Reverend Foster’s agreement that Francis lacks the strength to preach masks his deeper concern for the bishop’s condition.

The nearly one minute of silence which follows Reverend Foster’s warning is followed by Francis’s response. “John, God has given me a work to do there; I must deliver testimony. Besides preaching in Richmond, I am to hasten toward Baltimore.”

John says nothing. He looks to Bishop Moore, who quickly responds, “John, please collect Bishop Asbury’s chaise; he longs to preach this evening.” Without hesitation, John departs.

The young man John is the Reverend John Wesley Bond. For nearly the last three years, John has been the traveling companion of Francis Asbury. He, along with a driver, is charged with delivering the aging saint by horse-drawn carriage to each of Francis’s appointments. The 32-year-old preacher is actually far from young, admitted on trial at the Baltimore conference in 1810, six years ago. However, in light of the ecclesiastical experience in the room he just left, he is in the infant beginnings of his ministerial career.

John is an attentive and loving man, constantly caring for the ailing Asbury. In the spring of 1814, two years ago, Francis was stricken so hard with sickness that John was certain death was near. He summoned Francis’s long-time traveling companion and friend, Henry Boehm. The two men watched as Francis’s chest heaved with every breath, struggling as though their declining leader was near to strangling. For two weeks, when Francis found strength enough to cough it out, an ugly mucus discharge was expelled. This was the beginning of Francis’s current condition. His extreme loss of weight, difficulty in breathing, and violent body pains all began with this illness. Worse, his persistent cough—which now allows only three hours’ sleep each night and keeps John from sleeping as well—is no longer followed by an expelling of mucus; Francis’s debilitating coughs are now followed by a discharge of blood.

Loaded now into the four-wheeled closed carriage, Francis braces himself for travel. His frail arms lock at the elbows as his brittle, blemished hands clutch the wood bench in front of him. Seated beside him is the faithful John. Bishop Moore and Reverend Foster follow on horseback.

The driver eases the protected carriage toward the southern end of Richmond. The journey from Reverend Foster’s house on Main Street to the small Methodist church building at 19th and Franklin Streets is upon a smooth dirt road. Francis leans forward slightly and remarks to his young friend, “Road’s far superior to the roads of Western Pennsylvania. Roughest on the continent. Those sought my destruction.”

John smiles his reply, familiar with several of Asbury’s near-death experiences while traveling the treacherous paths over the Alleghany Mountains.

At the church, John disembarks. He immediately sets out to gently remove Francis from the carriage. It isn’t an easy task, carefully maneuvering Francis in a manner that doesn’t cause hurt or bring embarrassment to the bishop. John summons the help of Reverend Foster, requesting, “Attend the door. I have the bishop.”

Reverend Foster trots to the door and opens it, remaining outdoors as he patiently awaits John and his significant cargo. The young man carries Francis as a little child, the bishop’s thin back resting against his left arm as his legs hang lifelessly over his right.

Entering the building, John and Francis move to the front. A wave of gasps accompanies their arrival as the gravity of the bishop’s condition registers with each person viewing the skeletal frame of their beloved Asbury.

Every soul in attendance mournfully watches as John places Francis on a tabletop that resides within the pulpit. He gently sits Francis up, setting his legs to rest over the front side of the oak piece. Bracing Francis with his arms and reaching with his foot, he retrieves a small wooden stool to rest Francis’s failing feet upon. Continuing to support the bishop, John reaches one hand to carefully set the cloth-wrapped feet, swollen from an arthritic condition, onto the elevated aid—first the right foot, then the left.

With his task of setting up the bishop complete, John remains standing alongside his leader and friend. He offers to Francis, “I am here. Your congregation awaits.”

Facing the gathering of nearly one hundred people, Francis begins.

“From the book of Romans…”

Pause – –

“For He will finish the work…”

Pause – –

“And cut it short in righteousness: because a short work…”

Pause – –

“Will the Lord make upon the earth.”

“Do you work faithfully?”

“Continue to do it in the name and by the authority of the Father, Son…”

“And Holy Spirit…”

“Tell this rebellious generation they are already condemned…”

“And will be shortly damned: preach to them…”

“Like Moses from Mount Sinai and Ebal…”

“Like David…”

“Preach as if you had seen heaven…”

A loud coughing spell begins, the uncontrollable hacking echoing inside the sanctuary. The worshipers do their best, but they fear that each cough could be Bishop Francis Asbury’s last. Those who are familiar with Bishop Asbury are well aware that he has struggled with this condition for nearly two years: preaching tickles his throat, which results in the unwelcomed coughs. With the episode past, Francis begins again.

“Preach as if you had seen heaven…”

“And its celestial inhabitants…”

“And had hovered over the bottomless pit…”

“And beheld the tortures and heard the groans of the damned…”

For nearly one hour, Bishop Francis Asbury preaches to the Wesleyan faithful in Richmond, Virginia. The effort is a chore for both the preacher and his flock, as the good bishop pauses between sentences, battling the coughs and drawing what at times seems to his faithful congregation his last breath. The attendees patiently accept their leader’s condition, the effects furthering their endearment for Bishop Francis Asbury.

At the sermon’s end, John gently lifts Francis. The pair once again make their way to the rear of the church building, gratefully acknowledging flooded emotions flavored with praises to God for the outstanding life represented in the Methodist patriarch, Bishop Francis Asbury.

Outdoors, John safely delivers his bishop to the covered carriage. They return to spend the evening at the home of Reverend Foster.

Tuesday morning, March 26, 1816, finds Bishop Francis Asbury and John Wesley Bond traveling by covered carriage northward. Their plan is to complete the 55-mile trip to Fredericksburg, Virginia, on Thursday. The first day out seems to embrace the pair and their driver. The weather is pleasant, much warmer than expected for the end of March in Virginia. The agreeable conditions cause the men to rejoice over the fair weather. John informs Francis, “At this pace, we should arrive in Fredericksburg on Thursday.”

Francis smiles his approval. The men continue their trek until sundown.

Wednesday is not as favorable as Tuesday. The weather conditions have severely worsened. A driving cold rain greets John as he wanders outdoors, causing him to consider the circumstances. The temperatures are just above freezing. This is no time for the bishop to be outdoors.

As he returns indoors, John’s opinion to cease the day’s travel is confirmed by the hacking coughs of Francis. The bishop once again lies in a tightly roped bed. His breathing is difficult, difficult enough to cause concern. Next to Francis is a cotton cloth, stained with blood coughed up by the ailing bishop.

John informs him, “We shall remain here today. There is chance of freezing rain; no time for my bishop to be outdoors.”

Francis once again undergoes a brutal bout with his lungs. It is a struggle, but he eventually manages, “We must make haste for Baltimore.”

“We shall get to Baltimore, Bishop Asbury, but please—we must not travel today.”

Francis reluctantly nods his approval. John, however, is not so confident the pair will make it to Baltimore. Perhaps not even Fredericksburg…

Thursday’s weather allows for travel, and the driver and his two passengers set out around ten o’clock. No longer does Francis rise at four in the morning. He is fortunate to rise by eight o’clock, most days at nine—and that is on nights when the hacking coughs will allow only four hours of sleep. John once again sits beside his bishop as the driver slowly makes his way toward Fredericksburg.

But travel today is not as expected. Halfway through the day an unforeseen storm arises, sending cutting winds blowing through the vulnerable cabin of the carriage. Nearing four o’clock in the afternoon, John wisely counsels the driver to cease the journey. Despite Francis’s disappointment, he accepts John’s decision.

Friday morning, March 29, the bishop once again battles with the bloodied coughs. His appearance is noticeably less vibrant than in previous days. John worries for his bishop, wondering, Shall this be his last day?

John decides to gently approach the subject of travel. He inquires, “Bishop, I think it best we remain for a day. We can make for Fredericksburg tomorrow.”

Leaning forward in the chair, Francis clears his throat and responds, “We must make haste for Baltimore.” A severe coughing struggle follows his barely audible words. Reaching for his coughing rag, Francis utilizes the bloodied cloth to help complete his respiratory struggle. He nods to John, pointing toward the door.

Against his better judgment, John once again carefully places his bishop into the enclosed carriage. With Francis loaded, John moves to the front of the carriage and privately informs the driver, “We must not push for too much today. He appears out of sorts—almost, as he describes, ‘walking in living death.’ ”

“I understand; will proceed unhurried.”

“Thank you.”

The carriage sets out slowly. For the next few hours the driver does as instructed, maintaining a slow pace. John watches his beloved friend as each jolt of the rustic road brings a shout of pain, each ending with a muffled shout of “Hallelujah!” Nearing the early afternoon hour, it is clear that Francis can no longer handle the travel. His hands gripping the wooden bar in front of him consistently slip their grasp; he endures a bout of bodily pain every ten to fifteen minutes—a marked increase from the usual once every two hours. The resulting cries of pain seem to worsen the bishop’s condition. John is beginning to realize that the travel must cease.

With their destination of Fredericksburg, Virginia, out of reach, John ponders a solution. He is surprised when the bishop leans over and suggests, “Let us aim for my old friend George Arnold in Spotsylvania.”

John is happy that Francis is bringing the journey to a halt, but he is also concerned. He gently takes Francis’s hand and, with a soft tilt of his worried face, acknowledges Francis’s request. Leaning out the carriage window, John informs the driver, “Aim for Arnold’s.” The driver, familiar with the farm of George Arnold, responds with a wave of his hand.

Mr. George Arnold resides on a large estate consisting of 164 acres. It is an out-of-the-way location, completely rural, away from anything of note. One of Asbury’s typical back-country roads leads to the Arnold farm. George lives there with his wife and eight children, four sons and four daughters. His life is one of grateful support of the Methodist cause. It was in the early days of Bishop Asbury’s ministry in America, during the American Revolutionary War, that George Arnold experienced the preaching and teachings of the Wesleyan movement. In time, Mr. Arnold was not only convinced of his need of a savior, he was also persuaded to free his two slaves. With a new focus in life, the farmer George Arnold set out to spread the Methodist message, or more importantly, the universal message of the Gospel. For the last three decades, he has financially supported the building of several Methodist church buildings in the state of Virginia.

Unloading Francis from the carriage, John carries his beloved bishop into the home of Mr. Arnold. Directing them to the family bed, George assures John, “He will be comfortable there.”

John walks Francis to the edge of the bed and places the ailing bishop onto the duck-feather mattress. The soft pad engulfs Francis. From behind John, George’s wife helps her two daughters gently place a heavy quilt over Francis’s trembling body, adding, “This shall keep him warm.” Mrs. Arnold nods to her girls and the women depart.

George inquires of John, “The driver informs me you are heading to Fredericksburg; where to from there?”

John looks to Francis; the bishop’s eyes open and close sporadically. John responds, “The bishop wishes to attend the General Conference in May. He continues to insist, ‘I must make haste for Baltimore.’ ”

At the completion of John’s reply, the bishop attempts to clear his throat. John and George look to Francis. The ailing man forces his eyes open and informs them, “We no longer need to be in haste for Baltimore…”

Francis closes his eyes. The bishop’s response causes John to raises his hand to his eyes. He turns from Francis and weeps. The quiet sobs go unnoticed by the bishop, but they are clear to Mr. Arnold. George walks to John, places his sturdy hand on the itinerant’s back, and offers, “He shall see our Lord before long.”

“I know. It pains me so, but I know.”

For the next six hours Francis lies motionless, sleeping, in the Arnolds’ family bed. Around ten o’clock in the evening, the bishop finally awakes. He looks about the room for his companion. “John?”

“Yes, Bishop, I am here.”

“As well.” With this, Francis once again nods off to sleep.

For the next five hours, John and George watch as Francis battles bodily pain. He is no longer screaming in anguish—that ability has evidently expired—but it is clear from his facial and bodily contortions that Francis is wrestling with unbearable pain.

Around three in the morning, Bishop Asbury speaks a word. “John, my bodily affliction is growing worse.”

“I know, Bishop. I am praying for your relief.”

Kneeling next to Francis’s bed, John offers a word of prayer. “Almighty Father, we desire Your comforter, Your holy companion. Empower this brave bishop to experience Your peace which transcends all understanding…”

For nearly an hour, John and George kneel in prayer for their bishop.

Nearing dawn, Francis once again rests in sleep. His bodily struggles continue, but with much less severity. He no longer tosses and turns, but settles into one comfortable position. A look of contentment lights his face.

Nearing noon on Saturday, Mrs. Arnold enters the room carrying two bowls of soup and a loaf of bread. She motions to John and George, whispering, “Here, you must eat.”

The men quietly acknowledge her observation. Passing them the simple fare, she softly inquires, “Does he continue to struggle with the pain?”

John replies, “It seems to have subsided. He has slept since dawn.”

“That is good. Eat; you men are here if the bishop needs you.” The men endeavor to finish the soup and bread.

For the rest of the day and all of the evening, Bishop Asbury sleeps. His body barely moves. Concerned for his companion, around midnight John pulls back the quilt and touches Francis’s neck. “He is cooler than normal. His breathing is regular—not strong, but regular. He seems comfortable enough.”

“He is, John. Our beloved bishop is either returning or leaving. He waits upon God’s decision.”

At eleven o’clock on the Sabbath morning, Francis awakes. He calls to John, “I wish to sit upright.”

Startled by the request, John and George stumble to their feet, the wooden chairs they have been attempting to sleep in squeaking as they slide them across the wooden floor. John replies, “Bishop Asbury, you must lie down.”

“No, John; is it not time for meeting?”

Befuddled by Francis’s insistence, John looks to George and shrugs. “I suppose we should raise the bishop.” Both men come to his aid, gently raising Francis upright in the bed.

“I long to sit in a chair.”

Again, the men are startled by the request. George sets out to acquire an adequate chair. Racing out of the bedroom, he calls for his sons as he hastens down the home’s main hallway. “Reuben, Aaron, Hezekiah, Enoch, fetch me the big chair in the main room!”

Within moments, the boys return with a large cushioned chair. It is an odd piece of furniture, a gift to Mr. Arnold by a French general who aided the colonists in the struggle with Great Britain.

Setting the chair next to the bed, the boys join John and George in attempting to raise Francis from his feathered cocoon. George sternly admonishes, “Careful with the bishop, boys.” It takes a few minutes, but they soon have Francis sitting upright in the chair.

Mrs. Arnold, aware of her husband’s request, enters the room. “Shall I call for the doctor? It seems the bishop is on the mend.”

George and Mrs. Arnold, along with their boys and the daughters who are slowly making their way into the room, each look to John. John doesn’t know how to reply. First, he cannot believe that Francis is well enough to sit up; second, he has seen the devastating effects of Francis’s ailment as it has nearly destroyed his beloved friend. The thought enters John’s mind, How can he be well enough to attend a meeting?

In the silence of the room, Francis responds, much stronger than any of them expect. “John, no need for the doctor–he will only arrive in time to declare me dead!”

Sensing that God is giving a last reprieve—and perhaps a short one—John makes a request. “Please, George, hand me a Bible.” George reaches for the Bible on the table next to the bed and passes it to him.

John thumbs to the back of the sacred book. “Ah, yes, the twenty-first of the Apocalypse…”

“Now I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away. Also there was no more sea. Then I, John, saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from heaven saying, ‘Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people. God Himself will be with them and be their God. And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away.’

“Then He who sat on the throne said, ‘Behold, I make all things new.’ And He said to me, ‘Write, for these words are true and faithful.’ And He said to me, ‘It is done! I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End. I will give of the fountain of the water of life freely to him who thirsts. He who overcomes shall inherit all things, and I will be his God and he shall be My son. But the cowardly, unbelieving, abominable, murderers, sexually immoral, sorcerers, idolaters, and all liars shall have their part in the lake which burns with fire and brimstone, which is the second death.’ “[1]

As John reads, he is doing his best to focus on the Scriptures. His attention floats back and forth between the reading and the looks on the Arnold family’s faces. Each one is drawn to the growing smile on Francis’s face.

George pronounces, “The bishop beams!” The family rejoices in the elevated spirit of their beloved bishop.

Considering this God’s time for Francis’s last meeting, John opens up with a Charles Wesley hymn. The family sings along. Although he fails to make a sound, Francis mouths the words which for almost an entire century have brought healing to many throughout Europe and in parts of Asia and America.

After the song, John offers a prayer of thanks for the work of God through his humble and obedient servant, Bishop Francis Asbury. Francis continues to smile his thankfulness.

With the prayer complete, John makes a request. “Mrs. Arnold, do you have any more of the barley soup? Perhaps the bishop would enjoy a few spoonfuls.”

“I do.”

It’s not long before Mrs. Arnold returns. She offers a spoonful of the barley soup to Francis, gently raising the warm broth to the bishop’s lips. He attempts to suck in the steaming liquid. With the soup in his mouth, he begins to struggle. John is quick to notice, “He can’t swallow. Here, Bishop, spit it out.”

Leaning toward the wooden bowl John had taken from Mrs. Arnold, the bishop discharges the liquid into the container. John warns, “We mustn’t force too much.”

Sitting back against the chair, Francis opens his eyes and notices the anxiety on the face of his young companion. He wishes to inform the young man that all is well, but he is unable to speak.

Francis decides to gain the young preacher’s attention in another way; he raises one hand. The gesture surprises all in the room. Mr. Arnold observes, “A remarkable feat for one of so weak a condition.”

With one arm completely raised toward heaven, the bishop beams a wide grin.

The transformation of his beloved bishop causes John to realize that this is not an earthly smile. He drops to one knee before Francis and inquires, “Bishop, do you feel the Lord Jesus to be precious? Is He near?”

With all the strength he can gather, Bishop Francis Asbury raises both hands toward heaven. It is a difficult task, but he accomplishes his goal. With arms extended, the bishop opens his eyes. John thinks to himself, His body is dying, but his blue eyes continue to gleam.

Francis’s face continues to radiate. John and George look to each other and to the bishop, marveling at this last effort of praise.

George races to Francis’s side. John, now on both knees in front of his beloved companion, assures him, “Bishop Asbury, I am here.”

Francis lowers his hands, his smile relaxes, and his head begins to droop to one side.

John quickly raises his hands and cups the bishop’s face between them.

Francis’s breathing is slow and deliberate as his eyes slowly begin to close. A sigh escapes as his body begins to recline.

The growing weight of the bishop’s head in John’s hands indicates either a relapse into sickness or that the end is not far. He draws Francis close.

After a few minutes, leaning his head and body on his young companion, Bishop Francis Asbury breathes his last breath.

[1] Revelation 21:1-8 Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Jacob Young Account of Bishop Francis Asbury Personal Items

An interesting note about the death of Francis Asbury is that in his personal will, Francis left his clothes, his horse, books and manuscripts to his Co-Bishop, William McKendree. After the May 1st, General Conference in Baltimore, the conference where Asbury’s body was brought to from its temporary burial spot in Virginia for a proper funeral and burial, a young itinerant by the name of Jacob Young was given the task of delivering Francis’s items to Bishop McKendree, taking them across the Allegheny Mountains to Wheeling, Virginia.

The following is itinerant Jacob Young’s account of a peculiar event from this journey as noted in the autobiography of Jacob Young. The account is as follows:

“I traveled alone to Uniontown, Pennsylvania. I had charge of Bishop Asbury’s horse, and some books and clothes he had willed to Bishop McKendree. The books and clothes were packed in two valises, buckled together by two leather straps and laid across his old pack-saddle. There was another valise buckled behind the saddle, and all were handsomely covered by a large bear skin. I rode my own horse and led the Bishop’s. My horse and package resembled those horses and packages which carried silver from one part of the country to the other. Silver was scarce and the banks were trying to drain each other. As I passed by Gwinn’s old stand, near the foot of the Mountain, early in the morning, I saw a company of men standing in the door. Some of them pointed at me as I passed along; and, as I was just going into the mountain, the thought struck me that there might be danger ahead. I had not gone more than four or five miles, before I saw two men riding up behind me. I thought it was no use to be alarmed. I was then in my best days, physically, and I did not know of many who had much more activity and physical power. They rode up very pleasantly, and bid me good morning. I returned the compliment cheerily. They looked like a couple of strong men. They asked me if I lived in the west. I answered in the affirmative. They asked me how far I had been in the east. I answered, as far as the city of Baltimore. “How are the times in the west now?” I answered, pretty good. “Is plenty of money?” I answered, very scarce. He then cracked on my bear-skin, and said, “You appear to have plenty of it here.” I answered, no sir, there is no money there. This horse and package belonged to Bishop Francis Asbury, before his death, and he willed them to Bishop McKendree. I am conveying to Wheeling for him. The packages contain nothing but clothes, books, and manuscripts. They looked very much disappointed. One of them asked, “Is Bishop Asbury dead?” I answered, yes. “Well,” said he. “I have heard and seen him preach in my father’s house.” They paused a few moments, galloped off, and left me. It is impossible to tell what their intentions were, but I have always thought they intended to rob me.”

A splendid piece, Al. Very moving, indeed! I gained information that I did not know, and your writing style is excellent. Thanks, too, for the graphics. I copied the carriage picture, and I’ll add it to a PowerPoint lecture for one of my classes. Again, good work, Al. Many thanks.

Ken Kinghorn

Thank you, Dr. Kinghorn. I will inform the artist, Tyler Fegley, that you plan to use his carriage drawing in class lectures. He will love that!

Interesting & helpful

Thank you, Daryl. I’m glad you enjoyed it. Try the book. It will take you there!