The year is 1759; a man of German descent is struggling in Limerick County, Ireland. He is successful at his job, a talented carpenter. He is successful at his marriage, happily married to his wife Mary. He is a local preacher with the Wesleyan movement in the Limerick town of Ballingrane. What does this man of solid commitments desire? His problem? He desires to be a traveling preacher for John Wesley and Wesley just turned him down for a circuit. Instead, he placed Philip on a list of reserves.

Philip Embury is a direct relative to the German citizens forced out of the Palatine region along the Rhine in Germany in the beginning of the 18th century. His family eventually settled on the Southwell Estate in Limerick in 1709.

Lord Southwell is generous, but his unselfish sharing is ending. In 1759, the rents on the estate will triple. Philip and his wife Mary accept the inevitable, they must move. They also realize that they must do as many others in the community are doing, leave for America.

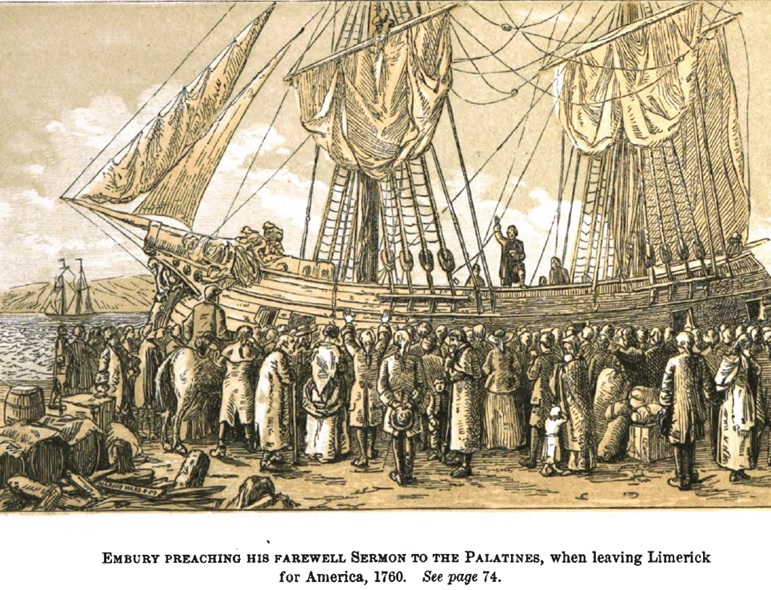

Philip, his wife Mary and several other families embark for the colonies in America. Among the group are Mr. and Mrs. Paul and Barbara Heck. They too, longtime residents of Ballingrane and friends with Philip and Mary Embury. All arrive America in August of 1760.

In New York, Philip quickly immerses himself in providing for his family. The same holds true for the other Methodist families like Paul and Barbara Heck. Although Philip never abandones family devotions, his preoccupation with making a living keeps him from preaching altogether.

In 1765, another ship full of Ballingrane residents arrives to the port in New York. These are the many friends of Philip and Mary; several of the men are his closest companions. By this time, many of Philip’s friends have sadly abandoned their religious practices, and have become comfortable with card playing and other sinful amusements. Surprising to the Embury and Heck families, several of these close friends of Philip are adamant in their disdain of religion.

Philip decides he will not participate with his changed friends. He patiently seeks to better his life in the new country of his choice.

One evening in the autumn of 1766, the usual gathering of men, loudly playing cards assembles a few houses down from the Embury and Heck families. The liquor flows freely, the abusive language as well. As the men continue in their state of depravity, Barbara Heck bursts into the room. Filled with rage for the ongoing, she sets out to end the debauched behavior. Pushing aside the men, she reaches over and around the inebriated gamblers, picks up the cards that lay on the table and throws them into the lit fireplace. Not content to stop, she gathers up the liquor and disposes of it as well into the fire. She delivers a condemning pronouncement and storms out of the home.

Making her way two doors down to the home of Philip Embury, she thrusts herself into his main room also. Startled at the unexpected intrusion, Philip stands to his feet. Barbara promptly places herself within inches of Philip’s face and delivers,

“Have you forgotten Ireland? God is going to require their blood at your hands.”

Not knowing what to say, Philip attempts to gather a response. Barbara interrupts,

“Brother Embury, you must preach, lest we shall all go to hell.”

Philip finally gains a reply,

“How can I preach, I have neither house nor congregation?”

“You can preach in your own house.”

Within a few days, Philip gives notice that he is going to preach. He does, to a congregation of five people. This is the beginning of the John Street Methodist Church in New York.

Hi, The Embury folk are my mother’s family. Philip Embury was a cousin of Barbara (nee Ruckle) Heck…Philips parents were Andreas Imberger (Andrew Embury) and Margarath Ruckle … It was All In The Family there… David Embury, Philips brother, is my ancestor. I have often visited the Blue church where the Heck family rests and where Barbara’s Methodist role is honored.

This past week I had an opportunity to Visit Worms and Mannheim, Germany where the family and associated families originated.

By a quirk of fate it seems, also by my mother’s family, that I am related to the same Southwell family that took the Palatine refugees to Co. Limerick…

ciao,

John R

Hello, John. I am fascinated with your family connections. The Embury and Heck story is rich. The Southwell family as well. In the opening book of the series, Black Country, I have devoted an entire chapter to the Palatine Germans in Ireland. The second book, Beggar Bishop, will follow the rest of Philip Embury and Barbara Heck’s story as it played out in Wesley’s church in New York. The Black Country chapter was one of the most interesting chapters to create, a rich history in a beautiful land. I was also drawn to the beautiful River Shannon. Thank you for the comment. Black Country is ready for shipping in two weeks, the first of May.

Hello Al and John –I’m new to following the Barbara Ruckle Heck and Philip Embury history connection, working hard on it and have been asked to do a group portrait of that very first Methodist worship service on Barrack Street. I’m knee deep in research and am thrilled to learn that you John, are a direct descendant of Philip’s brother David. The fact that you’re also of Southwell’s blood line must be a whole ‘nother fascinating story. Glad to see you’re keeping this important story in the forefront, Al. Thanks–Suzanne (ps–John, were you able to amend the detail in your book that Philip and Barbara were first cousins? Just curious.)

Hello, Suzanne. I’m glad to hear you are drawn to this amazing woman. In the second book of the Asbury Triptych Series trilogy, Beggar Bishop, the following appears in reference to the first Methodist meeting led by Philip Embury: “The initial meeting from his home on Barrack Street, had six attendees, Barbara went out and gathered four individuals. One of which was her African maid, Betty. For the first few months, these five individuals along with Philip made up the Wesleyan society in Manhattan. Not much of a beginning, but a solid foundation for sure.

The little congregation of six gained a beneficial advantage when Philip started preaching in the local almshouse. The almshouse was set up like those in England, a place where people out of work or in need of food or medical treatment could go for help. The houses were mostly run by thoughtful Christians who practiced Jesus’ teachings of the good Samaritan while at all times maintaining the Bible’s admonition ‘if anyone will not work, neither shall he eat.’ In addition to the downtrodden, several local, recently released prisoners would attend the meetings. The meetings soon grew beyond capacity. The scene was chaotic, many of the participants had to stand outdoors to hear Philip preach. The overcrowding reduced some as several of the prisoners who were receiving benefits from the almshouse became convinced that they should be working to earn an honest living.

Philip and the leaders of this new Wesleyan church moved the meetings to a sail loft on William Street. Here, the large open room used to work on the canvases which captured the winds aloft, pushing the large ships across the Atlantic ocean became the perfect location for many of the Manhattan Methodists to meet.

By 1767, the sail loft was becoming obsolete. The crowd of people soon filled the open space, flowing out of doors. Philip and the rest had to make a decision. In February of 1767, a strange looking fellow walked into the prayer meeting that night in the sail loft. His odd appearance startled several in the room. Their alarm of this uniformed British soldier, wearing an eye patch and with a large sword hanging at his side was not without just cause. Since the repealing of the Stamp Act one year before, the sight of a British soldier in full uniform led many to believe that further troubles were on the horizon. The increasing numbers of British soldiers showing up in the colonial city put many on watch. The gathering of the faithful was soon relieved to see the soldier bow in prayer with them.

This British soldier was Captain Thomas Webb. Captain Webb soon helped to engineer the leasing of the land and building of the Wesleyan chapel at 44 John Street. In 1768, the Manhattan Wesleyan society broke ground on the structure. As per the advice of Captain Webb, the structure was to be called a chapel and was to receive a large stone fireplace and chimney. These two measures were to ensure that the British colonial government would not consider the structure a church to compete with the Church of England. For by colonial law, dissenters like the Methodists were not allowed to construct places of worship. Also by English colonial law, the Methodists, along with every other citizen in the colonies were forced to financially support the Church of England. The ruling frustrated many. Disguised as a place of residence, the inside of the structure remained unfinished for some time. Eventually, the talented carpenter, Philip Embury, constructed the pews and pulpit for this new house of Wesleyan worship.

On October 30, 1768, Philip Embury preached his first sermon inside of Wesley’s chapel. In his simple manner, he urged the two hundred and fifty present to ‘Sow to yourselves in righteousness, reap in mercy; break up your fallow ground; for it is time to seek the Lord, till He come and rain righteousness upon you.’ From this hand-crafted pulpit, the Irish carpenter turned preacher ministered to many of the Manhattan citizens. Several of which who were prominent members of the colonial government and several of which who were local artisans of African descent. Philip Embury preached without income until the arrival of Joseph Pilmoor and Richard Boardman in the autumn of 1769. He was thankful to give up the pulpit to the authorized and qualified preachers. Soon afterwards, Philip and his wife, along with Paul Heck and his wife, Barbara, departed Manhattan for upstate New York, but not before ensuring that an itinerant’s apartment be constructed on the premises. In 1770, an adjacent parsonage was constructed and put into use for John Wesley’s missionaries, Pilmoor, and Boardman.

My name is Linda Case Heck. My mother was a Ruckle, daughter of Minnie Ruckle, from West Virginia who moved to Ohio with her husband Lloyd Weaver who was a Methodist Minister before his death in the 1960’s. I am married to Charles Heck from Urbana, Ohio. I believe he is a relative of Paul Heck…most of my relatives have passed away, but Gladys Ruckle Weaver Castle who is 91. She knows the names of her Ruckle Family that were her aunts and uncles. She lives in North Lewisburg, Ohio

All interesting to me.